First Impressions of King Philip’s War

Multiman Publishing recently released its latest strategy board game King Philip’s War, designed by John Poniske, and based on the conflict between English colonists and Native Americans in 1675 New England. Metacomet was the leader of the Wampanoag tribe whose name was anglicized in order to (hopefully) make him more palatable to the English. Metacomet’s father came up with “Philip”, a common English name. The honorific “King” was added because the Indians knew that the English called their leader “King”. Thus did “King Philip” make his debut.

I sat down with a friend of mine last week (he had also been eagerly anticipating King Philip’s War) and broke out the game for the first time. The rules are concise and organized well enough that we were able to have the game setup and underway within about 15 minutes. I took the English side and we dove right in.

Although the game rule book contains some background info, and extensive examples of play (which have drawn some negative comments on ConSimWorld), we just ignored that stuff and began playing. Neither of us had an inkling of tactics to employ and so resolved ourselves to learning the hard way. And we did…

Now, having completed one face-to-face game of King Philip’s War, I feel eminently qualified to opine. And so I shall.

First impressions are often good indicators of how we will ultimately judge a product, and this game made a good first impression. Having such little experience with the game, it’s hard to give a considered opinion, but the initial impressions were definitely favorable.

Quick Overview

The English player controls four colonies: Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Plymouth Colony. The colonists control infantry units, called Soldiers, and leaders. Soldiers can stack together to form “companies” and leaders provide stacking, movement and combat benefits to companies. Other than the generic leaders, called “Captains” the English have two “key” leaders: Benjamin Church and Josiah Winslow. These key leaders have additional capabilities.

The Indian player may control as many as nine distinct native tribes: Wampanoag, Sakonnett, Pocasset, Niantic, Narragansett, Nipmuck, Pocumtuck, Abenakis and Mohawk. Indian infantry units are called Warriors, which may stack together to form War Bands. Generic Indian leaders are called “Sachems” and the two “key” leaders are Canonchet and Metacomet (aka King Philip).

The board game map shows game “spaces” to regulate movement which may represent Indian villages, English settlements, or just plain open or neutral spaces. Black dotted lines connect the spaces, but near the center of each line a string of 1, 2 or 3 colored “pips” appear and indicate the actual movement point cost to cross. I have not seen this mechanism in other games and I thought it was a really handy way of managing the various movement point costs. I find it preferable to having to lookup terrain movement point costs or having to remember the value of color coded connector lines.

Some spaces are connected by rivers, and limited movement is allowed along these river lines. Settlements and villages have inherent defense strengths, with English forts providing even greater defensive benefits. There are also certain coastal settlements that function as ports, allowing the English (only) to perform “ocean movement”.

The colonists receive a steady stream of reinforcements from Europe.

Indian reinforcements arrive in a trickle from currently allied tribes. Unlike English casualties, Indian casualties may not normally re-enter the game (only certain combat events, such as “Massacre”, allow Indian units to come back from the casualty box). The best way for the Indian player to beef up his forces is through “Indian Diplomacy”, the game mechanism by which King Philip persuades additional tribes to join his alliance.

Like many point-to-point movement games, movement can be interrupted by enemy units attempting to “Intercept”. Conversely, players can attempt to avoid combat situations via “Evasion”.

Assuming that the moving Company/War Band has not been intercepted, has sufficient movement points remaining to enter a space occupied by enemy units, and that enemy unit has not successfully evaded, combat will ensue.

Benjamin Church

There are a number of generic (unnamed) leaders, but there are only four named leaders in the game: Church and Winslow for the English, and Metacomet (King Philip) and Canonchet for the Indians. Of the named leaders, Church and King Philip are crucially important for their respective sides.

Metacomet is the only Indian leader that can conduct “Indian Diplomacy” which allows him to possibly recruit one new tribe per turn. Without this influx of new warriors, the Indian side will suffer a crippling shortage of manpower.

Even more important to his team is Benjamin Church. Church may arrive anywhere between turn 1 and turn 6, depending on the luck of the dice. Before his arrival, the English colonists must operate under some grim disadvantages.

- Only 3 English Companies may be activated for movement each turn.

- Only 3 battles may be declared each turn.

- The English may not use 2 or 3 “pip” connections for movement or placing of battle markers (this is a serious limitation).

- Soldiers from different Colonies may not join to form Companies (i.e. may not stack together).

- Companies may not use river movement.

- The English may not roll for Indian Allies.

The Indian player must capitalize on the period before Church’s arrival, as all other measures of advantage will diminish as the game progresses. If the English get lucky and Church arrives on turns 1, 2, or 3, it will be a much tougher battle for the Indians. If, however, the opposite is true, the Indians can lay the foundation for tactical victory that may be irreversible.

Combat

Combat in King Philip’s War is an uncomplicated process with a few unusual conventions. Each side calculates its total number of strength points, which will include infantry units, villages/settlements, fortifications, and other modifiers such as Leaders, Muskets and Spies. Yes, the villages/settlements may possess strength points that defend even when unoccupied by infantry, or are added to the defender’s infantry total. Three dice are rolled: a red 6-sided die, a green 6-sided die and a special 6-sided Event die (see below).

The red die is cross-referenced with the number of English strength points involved in the combat to arrive at the total number of strength point losses inflicted on the Indians. The green die is cross-referenced with the number of Indian strength points present to figure the number of strength point losses inflicted on the English.

Here’s the unusual stuff.

First of all if the same number appears on the red and green dice, the battle ends instantly. This could be due to poor weather, timid leadership, or just plain getting lost.

The effects of the curious Event Die are determined next. If the sum of the red and green dice is an even number, the Event will affect the English. If an odd number, it will affect the Indians. The “effect” may be either good or bad, so it’s not always a good thing to be the “affected” guy.

- Ambush – Allows the affected side to get their licks in first, rather than the usual simultaneous combat results.

- Spy – The affected leader has a Spy attached to him, which is not a good thing and will negatively impact the leader in several ways (negative modifiers on Interception and Evasion die rolls, reduced movement allowance, reduced combat strength, and allowing enemy re-roll option).

- Guide – The affected leader has a Guide attached to him, which is a good occurrence and benefits the affected player in a roughly inverse manner to the Spy.

- Massacre – The opponent of the affected player has committed an atrocity and the affected player is rewarded with infantry reinforcement.

- Panic – The affected player’s force panics, thereby reducing his overall combat strength.

- Emergency Reinforcements – A beneficial column shift is granted to the affected player for the upcoming combat.

Losses are taken either by eliminating infantry strength points (i.e. flipping a full strength unit to its weakened side or destroying a weakened unit) or by taking hits on the defending space’s village, settlement or fort. Victory points are awarded for eliminating enemy units or leaders and for razing villages/settlements.

Let’s run through a combat example.

Positions just before English Movement Phase

English

- Benjamin Church (with a Spy in his camp) and a company of 5 Strength Points (SPs) located in the settlement of Lancaster in Massachusetts Bay Colony.

- An un-named Captain (leader), with attached Guide, and a company of 2 SP are located in the settlement of Medford.

Indian

- A War Band of 1 SP located on the razed English settlement of Billerica.

- An un-named Sachem (leader), with a War Band of 3 SP located in an Abenakis village.

- Metacomet (King Philip), with a War Band of 2 SP located in an Abenakis village. (note that Metacomet is allowed to stack with Indian units regardless of Tribe)

English Movement

- Church moves his force 2 movement points to the neutral area, and then pays an additional 2 movement points to place the Battle Marker to indicate an attack on the Abenakis Indian War Band with the Sachem in the village. Note that Church’s company had just enough movement points to get there. The English normal movement point allowance is 5, but Church has a Spy attached to him so his movement is reduced by -1. Therefore, the 4 remaining movement points are just enough to get him across the two “2-pip” movement lines.

- The Massachusetts Captain in Medford takes his company and spends the 3 movement points required to place a Battle Marker on the Indian War Band in the razed settlement of Billerica. Note that, if Church was not yet in the game, the English would not be able to make this move because it is a 3-pip crossing and they are limited to 1-pip crossings until Church arrives.

- Battle markers are placed to indicate where battles may take place.

Interception

Immediately after placement of Battle Markers, any of defender’s units adjacent to the battle space may attempt to Intercept the Battle Marker. The Indian player feels that the defenders in the Abenakis village will be sufficient to hold the space, but that the razed town of Billerica will be lost if not supported. Therefore an attempt will be made to Intercept into Billerica. Note: Since there is already a Sachem (leader) in the Abenakis village and, since there cannot be more than one leader in a space, King Philip would not be eligible to Intercept into the space, so all or part of his War Band would have to attempt the Interception without him and the die roll would not benefit from his “Key Leader” modifier. Another reason that the Interception into Billerica sounds like a better option.

A final modified die roll of 5 or more is now required for a successful Interception into Billerica to succeed. Modifiers to the die roll are as follows:

- -2 for the two “pips” between King Philip and Billerica.

- +2 for a Key Leader (King Philip).

So the net modifier is 0. Therefore the Indian player must roll a 5 or greater. Unfortunately, he rolls a 4 and cannot Intercept.

Evasion

Having failed the Interception roll the Indian player decides that, discretion being the better part of valor, it may be wiser to bail out of Billerica than to remain there and be eliminated, with replacements being scarce as they are. He will attempt an Evasion roll, declaring the “escape space” as the village where King Philip is. The Indian player can successfully Evade on a die roll of 5 or higher (whereas the English must roll 7 or higher) and there will be no modifiers to this roll since there are no Leaders, Spies or Guides in the hex. (Note: The other War Band that’s being attacked by Church may NOT attempt to Evade since Church in is the attacking Company – see rule 13.1)

The evasion die roll is 5, allowing the Indian War Band to escape to the safety of King Philip’s current location. Since the vacated space is a razed settlement, which is treated the same as a neutral/empty space, the attacking English units may advance. There will be no battle so the Battle marker is flipped to its “Battle Fought” side.

Battle Roll

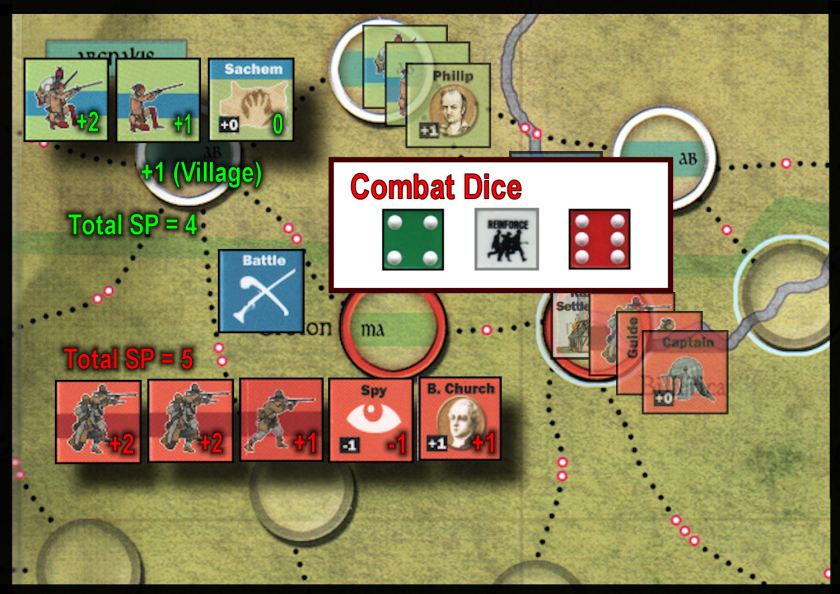

So, we’re left with only one battle, between Church’s company and the War Band in the Abenakis village. The English have a total of 5 SPs: 1 SP each for the 5 soldiers, +1 SP for the leader (Church), and -1 for the attached Spy. The Indians have a total of 4 SPs: 1 SP each for the 3 Warriors, 0 SP for the Sachem, and +1 SP for the undamaged Village itself. So the English will be using the “5 SP” column of the Combat Results table and the Indians will be using the “4 SP” column, subject to modification by Events. The red, green, and Event dice are rolled by the attacker with the following results:

- Red (English) die roll = 6

- Green (Indian) die roll = 4

- Event die roll = “Emergency Reinforcements”

Since the total of green and red dice = 10, which is an even number, the “affected” player will be the English.

The “Emergency Reinforcements” event states that the “affected” player gets a column shift in his favor on the Combat Results table, so the English will be using the “6 SP” column rather than the “5 SP” column to resolve this combat, and the Indians remain on the “4 SP” column.

The fact that Church has a Spy attached to him allows the Indian to force a re-roll of any one of the three dice just rolled. The issue with using the Spy is that, once used, the Spy is removed from play. While it is tempting to use the Spy now to try and reduce the the English “6” die roll, the Indian player decides to hold off, leaving the Spy in place in the midst of Church’s camp for use on a more critical future battle. So, all die rolls remain intact.

Looking at the Combat Results table, we cross reference each player’s die roll with their current SP levels to arrive at the combat result (which is the number of SPs lost). The Indian scores 1 SP hit against the English (cross-reference the “4 SP” column with the Indian die roll of 4), and the English score 3 hits against the Indians (cross-reference the “6 SP” column with the English die roll of 6).

The English player decides to absorb his 1 SP loss by flipping over one of the full strength Soldier units to its half strength side. He could also have eliminated the existing half strength soldier, but the removal of a unit from the map would give the Indian player +1 Victory Point, and the English decided against that. (Note: the disadvantage to keeping a lot of half strength units on the map is that they count, for stacking purposes, the same as a full strength unit)

The Indian decision requires a bit more thought. He must eliminate 3 SPs total. He can eliminate all 3 Warrior SPs and leave the Village totally intact, which would allow him to retain control of the +1 SP strength of the Village since the English may not enter a non-razed Village hex. He could then possibly reinforce the Village on his next turn and save it from English control. The down side of the approach is that, by eliminating all his combat units, he’d have to eliminate the Captain (leader) as well, which would put the leader out of action for two full Game Turns. In addition, by removing two Warrior units (the full strength and the half strength), he’d be giving the English 2 Victory points.

He could also decide to take 1 hit on the Village (making it a “Raided” Village) and suffer 2 SPs on his Warriors. That would still prevent the English from receiving a Victory Point for razing the Village and would leave a single Indian Warrior strength point alive. But he’d have to give up a Victory point for the removed Warrior unit.

Alternatively, he could choose to suffer 1 SP on his Warrior units by flipping the full strength Warrior unit to its half strength side, and inflict two hits on his Village, thereby making it a “razed” Village. Even though no Warrior units would be physically removed in this scenario, the British would still gain a Victory Point for the razed Village.

So our hypothetical Indian player decides to go with the second option: 1 hit on the Village, making it a “Raided” village, and 2 SPs on the Warriors, leaving him with one half strength Warrior unit and the Sachem (leader). Church and his company may not advance into the attacked Abenakis Village because (a) there is still a Warrior unit there and (b) the Village is not yet razed. The English collect one Victory Point, the Battle marker is flipped to its “Battle Fought” side and the Combat Phase ends.

Winning the Game

The game may end instantly upon either player achieving his “Automatic” victory conditions. Otherwise the game ends at the end of turn 9 with the player with the most accumulated victory points being the winner.

Automatic Victory Conditions for the English:

- Accumulate 30 or more Victory Points.

- Both King Philip and Canonchet (Indian Leaders) are either dead or on the Game Turn Track (i.e. temporarily out of play due to being wounded).

Automatic Victory Conditions for the Indians:

- Accumulate 30 or more Victory Points.

- Both Boston and Plymouth have been razed.

There is an optional rule for a shorter game which cuts the number of Game Turns in half, so this game should potentially be suitable for any type of competitive or tournament play.

Summary

It was an engaging game, keeping my full attention for the entire 3 hours it took to complete. There is quite a bit of emphasis placed on “razing” English settlements and Indian villages; maybe more than I cared for. But given the nature of the conflict this board game represents, I suppose that’s appropriate and by design. My biggest mistake, and I believe the main reason I lost the game, was that I focused too much on engaging enemy War Bands and not enough time attacking and razing villages. You have to overcome the standard war game mentality of supposing that the destruction of the enemy army is always the main objective.

After completing my first play of any new game I usually spend a few minutes reviewing the progress of the game, the flow of the system, and the general feel of how it “played”. If I find myself already thinking ahead to strategies and tactics that can be employed the “next time”, that’s an affirmative reflection on the game, and was definitely the case with King Philip’s War.

After I have a few more completed games under my belt, I may expand on this review or modify it as appropriate. But for now I’m giving King Philip’s War “one thumb up”.