By Harvey Mossman

Last year, our wargaming group in Long Island decided to play Le Vol de l’Aigle via email with myself as umpire. It was an extremely fascinating experience. We chose the 1806 Prussian campaign that culminated in the famous dual battles of Jena- Auerstadt because the armies were fairly evenly matched in numbers and opposing forces were not so distant from each other that enemy contact would be unduly delayed.

Since I knew the rules, I became the umpire for the entire campaign. The campaign was played over the course of 2013 with players submitting moves twice a week. Players were assigned to command individual corps or division level maneuver elements. Participants inhabited 4 different states with some living in different time zones. Each player was expected to submit his orders via email. Players did not know the identity or emails of any other participants (even players on the same side) so that no information could be exchanged outside the simulation without going through me. I collected players orders, plotted all of the units movements on the game map and then issued intelligence reports about enemy contact. As the umpire, I also had to track rates of march, routes of march, fatigue generated by movement and combat, combat losses and changes in unit morale. Fortunately I was able to devise an easy Excel spreadsheet (which I may append to a future article on umpiring the system). This greatly simplified the bookkeeping.

As umpire, expect a significant amount of work. Let’s look at how the game turn flows through the eyes of one corps commander. Davout will send me orders for his 3 divisions. I developed a simple email template for each commander to use so that they reported the unit starting position, the route of march, the duration of march in hours and their expected end of march objective. There was also a space to add any specific notations such as rules of engagement for the troops. Each order was given a timestamp when it was written. Normally each day of the game would begin at 0600 hrs. when Corps commanders would issue there orders to their divisions for that day. These orders were sent via email to me. I then had to map out their units route of March, distance traveled, calculate fatigue accumulated from the March, calculate the distance from the unit to its corps headquarters, timestamp and issue a report of where the unit ended its march and its overall condition. I also had to calculate time it would take for reports from their divisions to reach Corps headquarters. As the timeclock advanced I waited until the calculated time before sending an email to the players with their reports from their division commanders. I advanced the time each day based on the general level of activity. The shortest increment was one hour. The largest increment was 6 hours. It all depended on how much activity, messaging and order writing occurred. This telescoping timeframe allowed the game to move more quickly during periods of inactivity or prolonged marching to contact. In a later article I will try to help aspiring umpires with tips on managing the flow of all of this information.

Playing an umpired game is probably about as close as many of us will ever come to commanding a 19th-century military organization. There was complete fog of war in the sense that players were only fed information they could realistically know about based on their unit’s positions. There was a random chance that messengers and scouts would get lost or captured and, indeed this played a somewhat ironic role in our own campaign.

– Karl von Clausewitz

The players were also immersed in a fairly realistic simulation of 19th-century communication. Orders that were issued took time to travel to units, to be acted on by subordinates and for reports to return to the commander. To many in the campaign, this sometimes proved maddening as they were faced with realistic time delays, misinterpretation of written orders and security failures when liaison officers got lost or were captured. When we play hex and counter wargames, our decisions are based upon unrealistically accurate information about the strength and location of our opponent. We also know our commands will be followed instantaneously and our unit’s reactions to enemy maneuvers will be assured. However, the Vol de l’Aigle robs you of your omniscience and players felt this acutely. For many, this led to indecision, excessive cautiousness, loss of focus on the objective and outright strategic and tactical blunders. At the end of this campaign, the participants universally had a much greater appreciation for the limitations commanders of the 19th century experienced and better understood how seemingly unthinkable historical mistakes occurred because of insufficient information and time/space impediments.

The Campaign Begins

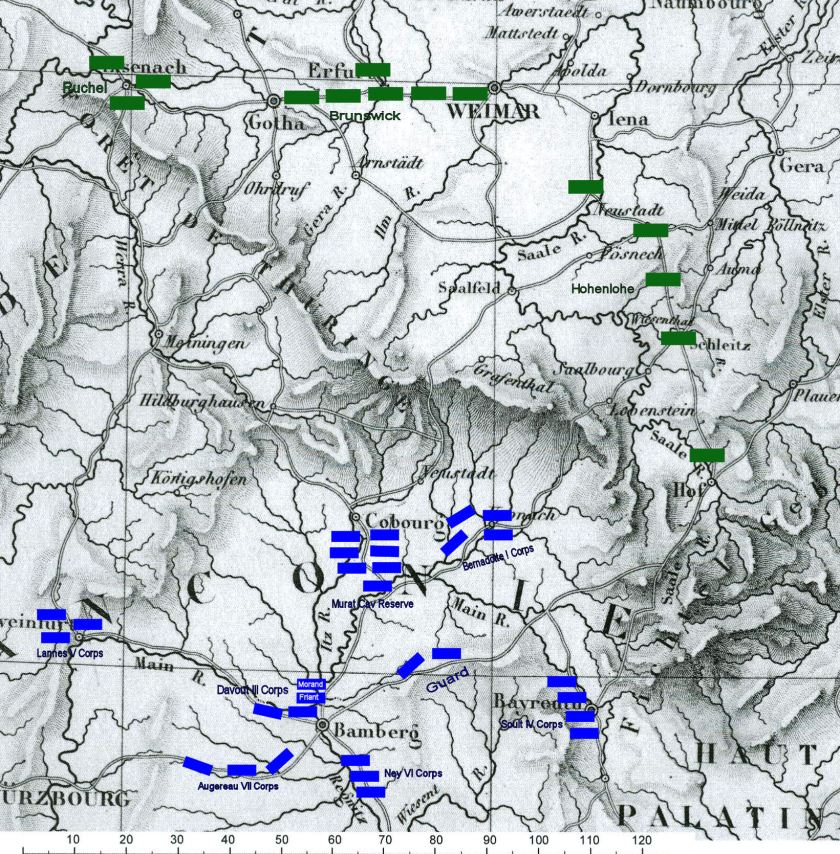

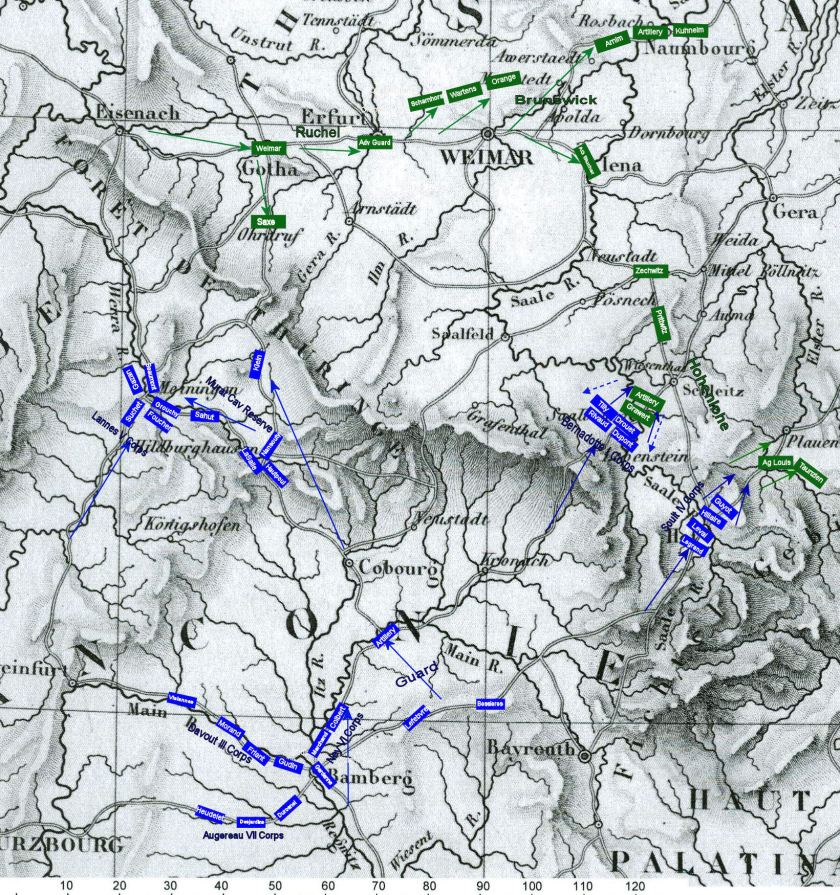

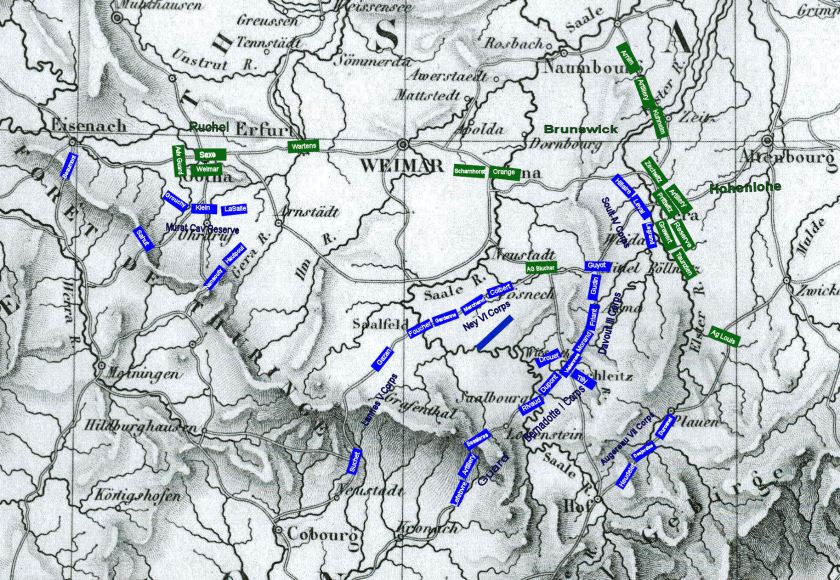

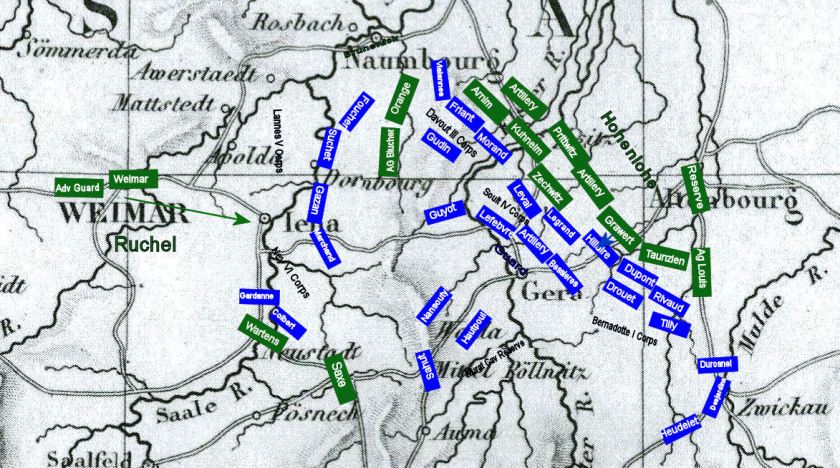

It is now October 11, 1806 and we transport ourselves to the Prussian frontier where Napoleon has gathered Le Grande Armee. Prussia, which should’ve joined the war against Napoleon in 1805 now chafes at restriction the Emperor has tried to impose on them. They decide that war is the only course of action to humble this Corsican Ogre. Napoleon assembles his Grande Armee on the Prussian frontier. He has decided on a quick, decisive invasion to knock Prussian out of the war before any possible Russian intervention. The positions of the units are depicted on the map below.

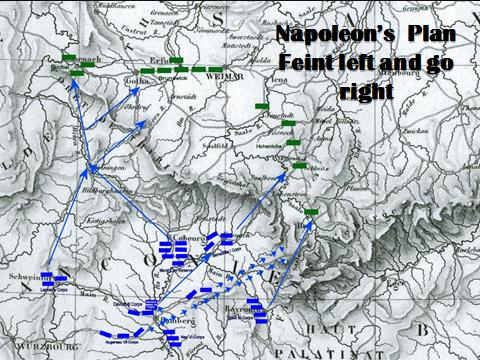

Napoleon’s plan was absurdly simple but well thought out.

“To all commanders; Campaign concept and general orders.

The army will aggressively cross the Foret De Thuringe range and concentrate in the vicinity of Gera with the aim of bringing the main Prussian army to decisive battle in the Weimar-Altenbourg-Leipzig triangle. The point of greatest danger will be while crossing the Thurignen passes. The cavalry corps, with support from V Corps will demonstrate to the west near Gotha to fix the enemy’s attention while the bulk of the army moves northeast toward Gera. The cavalry corps and V Corps will avoid decisive engagement by the enemy and once the main body has crossed the Thuringen hills, they will march east to become the army’s reserve.”

Simply put, Napoleon was feinting left and going right with his main force. Once the westward feint was complete, the feinting forces would close up on his right hook and serve as the reserve for the Army. We shall see in the debriefing how this adhered to many of the principles of war.

Despite these rather straightforward arrangements, things start to go wrong for Napoleon almost immediately. Marshall Murat decides that each of his division commanders should be notified about the entire plan for the upcoming campaign. He sends staff officers, each carrying the entire campaign plan, in all directions to notify his subordinate units. . Fate intervenes and one is captured. The entire campaign plan ends up in the hands of the commander of the Prussian Right Wing, Ruchel, who quickly forwards it to the commander of Prussian forces, the Duke of Brunswick. After some debate, the Prussian commanders decide that their impossible luck is just that… impossible and believe this to be an enemy ruse. Ironically, when Murat commits a 2nd gaffe this first day of the campaign resulting in a delay of his planned demonstration on the Prussian right wing, it only reinforces the belief that the captured French campaign plan is an enemy trick. On such little turns of fate is history made!

An order that can be misunderstood will be misunderstood.

– Napoleon

But Murat is not through spoiling Napoleon’s day. He misinterprets an order from Napoleon regarding the timing and route of march of the cavalry’s feint on the left.

“To Murat. Cavalry Reserve (7 div., 23,000)

Take your corps via Cobourg through Moiningen to secure the mountain passes leading to Eisenach and Gotha. Clear Moiningen by Oct. 15. Act aggressively to occupy the attention of the enemy but do not let yourself be engaged in a major battle with enemy infantry. If the enemy is weak, be prepared to advance to Erfurt and Weimar to cover the assembly of the main army at Gotha. If the enemy is present in more than corps strength then attempt to hold the passes but fall back to the Werra River if pressed.”

The word “clear” was used by Napoleon simply to state that Murat should be through the town of Moiningen by October 15 but Murat interpreted this as meaning there were enemy troops in Moiningen that had to be cleared out of the town before he could proceed on his march.

“As you are also aware, his majesty has bidden that we act aggressively against enemy forces…. Curiously in his latest dispatch to me Napoleon has also commanded that we “Clear Meiningen by Oct. 15”, from which I can only presume that his majesty is aware of some significant force to be holding that town? … it would be most prudent that we plan to defeat any enemy forces at Meiningen.”

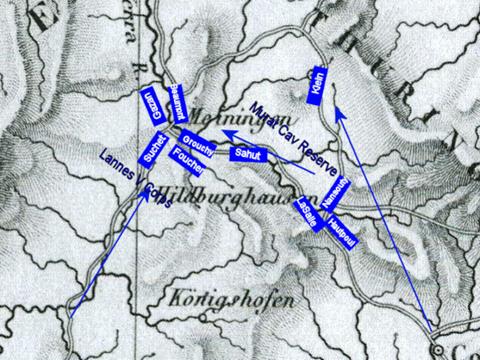

Murat immediately calls for help from Lannes 5th Corps and starts coordinating with Lannes to surround and assault the town from all sides. This leads to a massive traffic jam and a delay in his “aggressive demonstration” around Gotha.

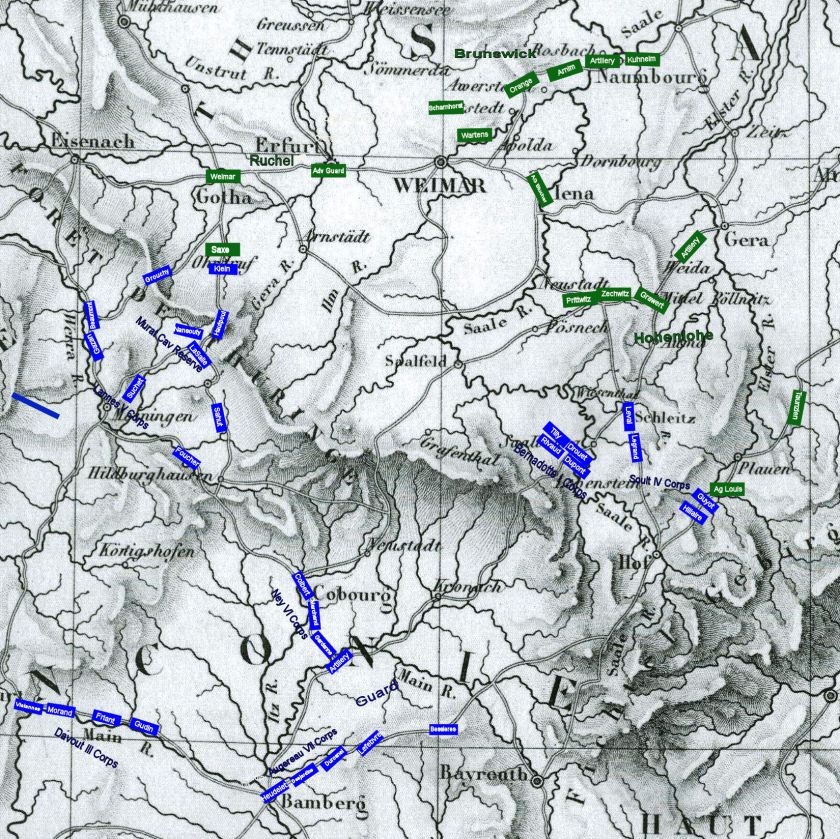

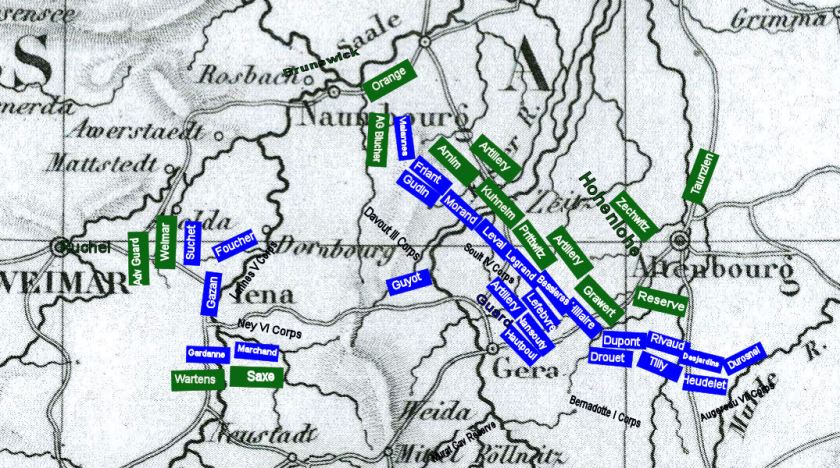

Despite the confusion on his left, the main body of the French Army moving eastward proceeds smartly through 2 passes in the mountains and makes first contact with the Prussians. Bernadotte suffers an early repulse. Soult is successful in clearing through the pass and forcing the Prussians to retreat to the Northeast.

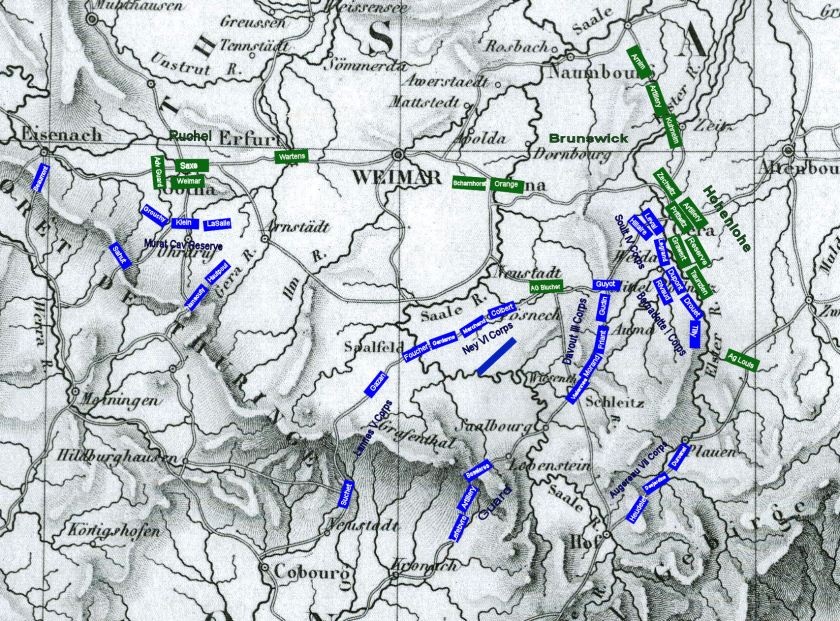

By October 12, the Moiningen debacle has delayed Murat and Lannes demonstration around Gotha. Bernadotte and Soult are already through the pass in the East and have attracted the attention of the bulk of the Prussian forces. The plan to feint left is now somewhat compromised. Yet the Prussians are still not sure that this is the main enemy force approaching them in the East. The Prussians are slow to concentrate and decide to fall back to the town of Neustadt by dusk on October 12.

On the morning of October 13, Murat’s forces have finally gotten the attention of Ruchel in the West. Murat’s cavalry engages Weimar and Saxe. In the East, the Prussians fall back and decide to concentrate around the town of Gera. Lannes is now ordered to March east to join the main Army and serve as its reserve.

Murat decides to press his attack on Gotha unaware that Lannes has been summoned East by Napoleon. Beaumont’s division of Murat’s Cavalry Reserve Corps tries to outflank Gotha but is stopped by the Prussian Advance Guard.

Weimar and Saxe are successful in repulsing Murat’s cavalry and push them back to the passes. The Advance Guard of the Prussians holds off Beaumont. In the East Bernadotte rests his Corps while Soult marches north towards Gera.

By nightfall October 13, the Duke of Brunswick is faced with a dilemma. He is getting first reports of an attack around Gotha and he is faced with an advance of French troops on Gera. Still unsure which is the main thrust, he keeps his units centrally placed north of Jena ready to respond in either direction once he can more definitively identify the main French advance. Unfortunately, information is maddeningly slow in coming and the captured French campaign plan still nags at his mind. It is taking his staff officers at least 6 hours to reach the area of Gotha and 6 hours to return with information. Therefore, any information he receives is already 12 hours old and his quickest response will take an additional 6 hours to return to Gotha. Similarly, Gera is 4 hours away resulting in a 12 hour command and reaction cycle. It is infinitely clear to him that he must rely on the initiative of his leaders on the spot to control and contain the situation until his army can react.

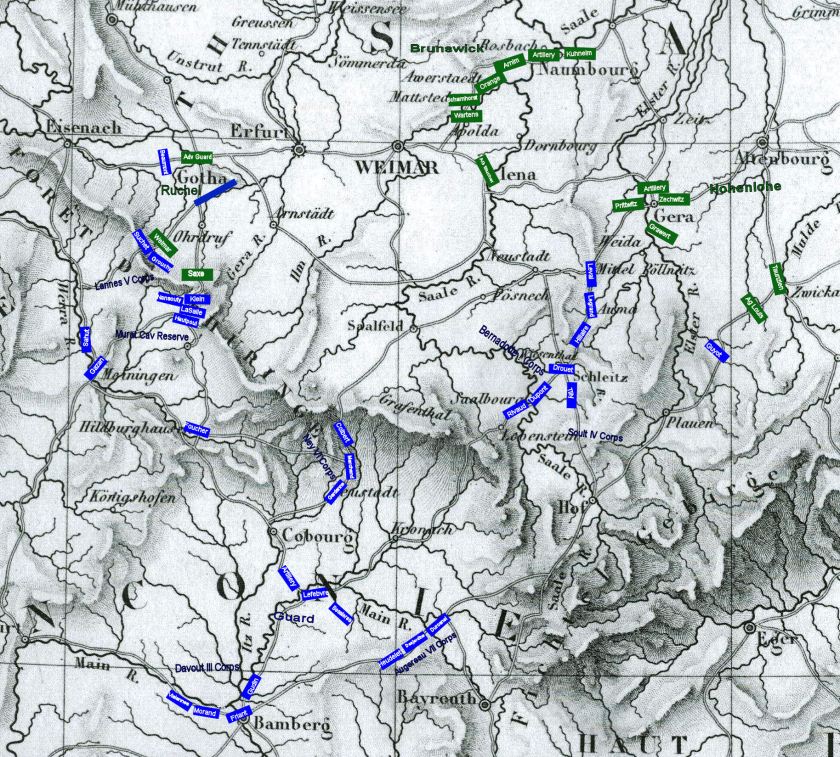

On the morning of October 14, both flanks are active. Murat devises a plan to try to tempt Saxe South across the pass in hopes of annihilating him with 4 cavalry divisions as he debouches from the pass. Saxe and Weimar have orders to hold Gotha which is the extreme right flank of the Prussian army and correctly withdraw in that direction. Murat’s trap is foiled!

In the East, advance units of Soult Corps discover Prince Hohenlohe entrenched at Gera across the river. Hohenlohe is in an excellent position to smash Soult Corps as the forward element of the French army has no support just yet. He hesitates to attack because he does not have complete information about follow-up French forces and a critical moment in the campaign passes with indecision. Bernadotte, unintentionally acting very historically, continues to rest his corps at Schleitz despite having received orders to advance and support Soult. Hohenlohe continues to concentrate on Gera.

Meanwhile Brunswick starts to move his units south in an effort to fix the location of the main French forces and close the gap between himself and Hohenlohe. Blucher is sent to reconnoiter and ends up at Neustadt. Unknown to him, he has three French columns converging on his position…..

On October 15, Brunswick finally decides to commit his forces. Succumbing to pleas for help from Ruchel, he sends one division westward, thereby weakening his concentration of forces towards what he is beginning to believe is the main French push at Gera. Wartens starts to march to Ruchel in what will be an indecisive and irrelevant theater.

Soult deploys across the River from Hohenlohe’s position. Hohenlohe is reinforced by General Kalkrueth with 2 divisions and an artillery division. Hohenlohe once again hesitates to attack and prefers to wait for these reinforcing divisions to fully come up before launching an assault across the river at Soult’s isolated Corps. In all likelihood, Soult would’ve been destroyed.

Meanwhile, Blucher marches his division towards Schleitz putting his head more firmly in the surrounding noose of French columns converging on him from three directions.

Murat receives orders to March east at all speed because Napoleon believes the decisive engagement will be there. He starts a cross country march to Saalfield with his Curraissiers and then on to Neustadt. Blucher finally realizes the danger he is in and retreats back to Neustadt and receives orders to hold there to put a crimp in the French concentration.

Wartens, having reached Erfurt, misunderstands an order when he was told to March South to Arnstadt. This most likely would have intercepted Murat’s Curraissiers heading east and prevented them from taking part in the upcoming battles around Jena and Neustadt.

Davout, with orders from Napoleon, demands Bernadotte follow him Northeast towards Gera however Bernadotte continues to rest his men ignoring Davout’s pleas. (I will note here that the player acting as Bernadotte was not trying to act particularly historical, but had legitimate, though somewhat exaggerated concerns for the fatigue his units had accumulated in his initial march and repulse at the hands of the Prussians).

It is not until nightfall that Bernadotte decides to move and arrives in the nick of time to take up a flank position adjacent to Soult. By the morning of October 16, Soult has been reinforced by Bernadotte and any chance of Hohenlohe annihilating the advanced French units has passed.

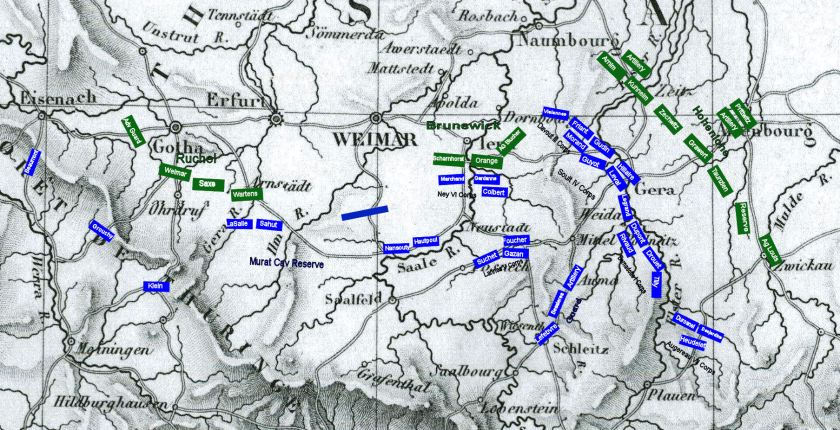

On the morning of October 16, Murat has his dragoons demonstrate in front of Gotha to conceal his march east with the cuirassiers.

On the Prussian side, Wartens arrives with Ruchel and Ruchel realizes that Wartens has misinterpreted his orders. He immediately sends him to march down the road towards Arnstadt. Unfortunately, Wartens is too late as Murat’s Curraissiers have already reached the road and are marching east towards Neustadt.

In the east, Blucher has almost extricated himself from converging French columns but he is assaulted by Ney’s whole corps and is badly defeated. He retreats north with his shattered division.

Napoleon now has his army strategically situated in the central position between the Prussian forces in Gotha and the Prussian concentration around Gera. All elements of his Army are concentrating towards Gera with only a small group of cavalry tying down 4 divisions of Prussians around Gotha. Although Murat’s initial misinterpretation of the situation around Moiningen could have led to complete failure of Napoleon’s feint to the West, his ploy has managed to divert one quarter of the Prussian forces from the decisive area of engagement further to the east.

Murat’s cavalry screens Ruchel who does not yet make any effort to test the French lines. Murat continues his March to Neustadt uninterrupted. The main battle lines at Gera form up as Augereau now threatens the left flank of the Prussian line. However, Hohenlohe has been reinforced by general Kalkreuth. At this moment, Prussian and French strength is roughly equal along the main battle lines and Hohenlohe still hesitates to force a general engagement before the French are further reinforced.

At 1300 hrs., Ruchel finally decides to push forward and see what’s in front of him. He also strongly urges Wartens on to Arnstadt.

The French cavalry screen withdraws. Murat’s forces have made a 48 hour forced march and arrive in the vicinity of Neustadt exhausted as Lannes’ forces also arrive and are now in a position to force an engagement with Brunswick’s forces in the area of Jena.

Napoleon arrives in the vicinity of Gera and decides to wait to attack Hohenlohe until the morning. The late hour and the wish to have all his forces at hand factor into this decision. Napoleon will be surprised by Hohenlohe’s next move.

Hohenlohe again hesitates to attack and orders a general withdrawal during the night. This increases the distance between his commanding officer, the Duke of Brunswick’s forces. He also abandons an extremely strong defensive position along the Elster River. He forms a line slightly to the Northeast but he does not withdraw far enough that the French will not be able to catch him the next day. In essence he has given up a very defensible position and has ceded the central position and the initiative to the French. The retrograde movement greatly increases his lines of communication to Brunswick. The French are now able to shift forces and get messages back and forth within their own lines in a matter of an hour or two but Prussian communications follows a circuitous path through Naumbourg taking more than 12 hours for two-way communications.

Hohenlohe again hesitates to attack and orders a general withdrawal during the night. This increases the distance between his commanding officer, the Duke of Brunswick’s forces. He also abandons an extremely strong defensive position along the Elster River. He forms a line slightly to the Northeast but he does not withdraw far enough that the French will not be able to catch him the next day. In essence he has given up a very defensible position and has ceded the central position and the initiative to the French. The retrograde movement greatly increases his lines of communication to Brunswick. The French are now able to shift forces and get messages back and forth within their own lines in a matter of an hour or two but Prussian communications follows a circuitous path through Naumbourg taking more than 12 hours for two-way communications.

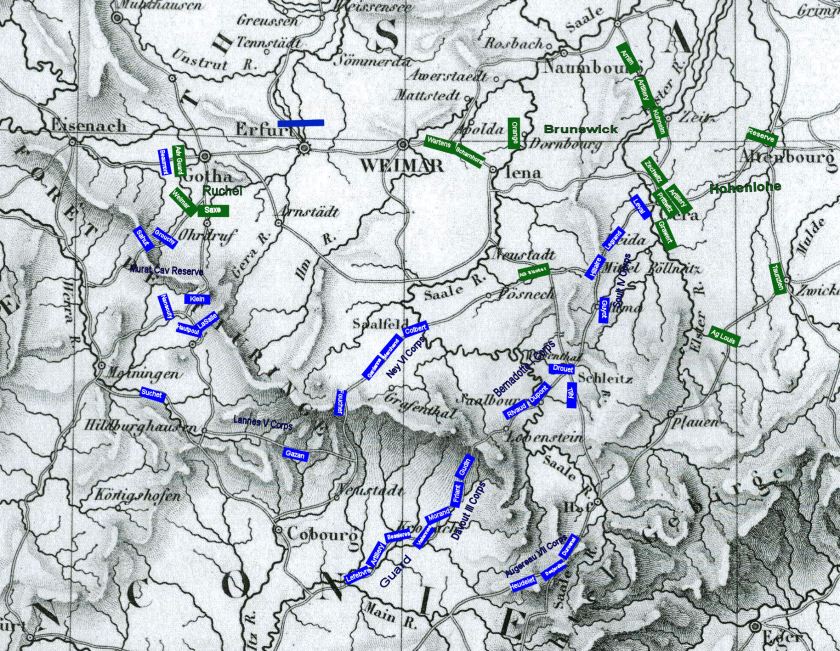

The morning of the 17th brings surprises in the West and in the East. In the West the French have broken contact spoiling a well-planned attack by Ruchel. Napoleon has now concentrated the Imperial Guard and two of Murat’s Curraissiers to serve as a reserve.

By early morning, Wartens and Saxe, finally realizing there are only screening forces in front of them, quickly march towards Neustadt leaving two divisions of the Prussians to guard Gotha. The French cavalry are nowhere to be found.

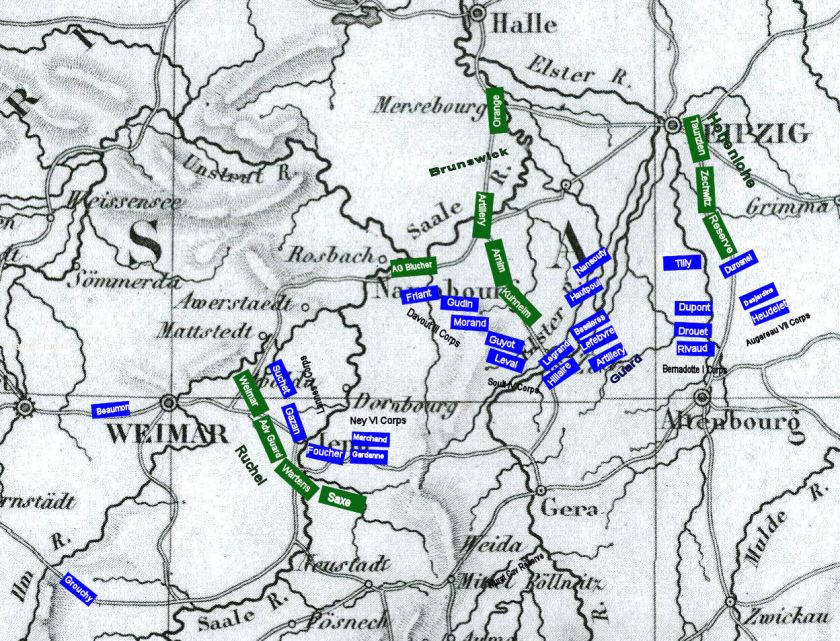

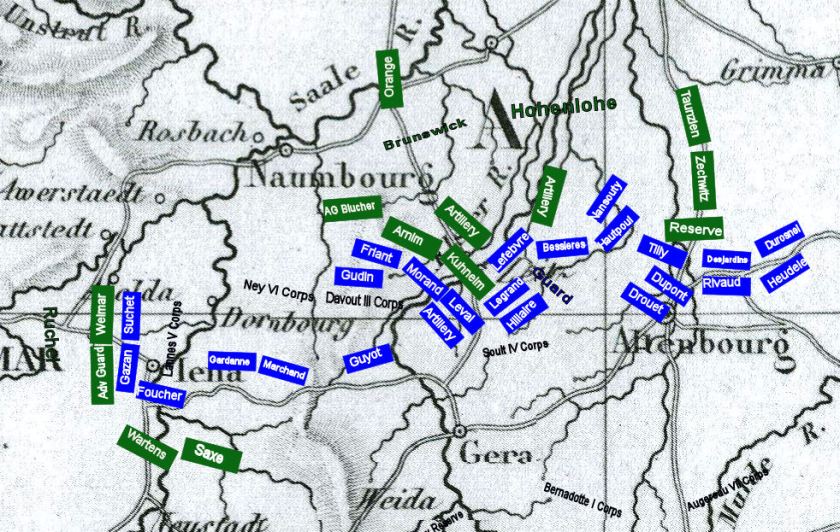

Further East, the battle of Jena begins with Lannes and Ney attacking Brunswick’s small force of three divisions one of which, Blucher, has been devastated the day before. Meanwhile, at Gera, Napoleon orders the French forward to regain contact with the Prussians and determine their new location.

Davout finds the Prussian right flank as Bernadotte sends cavalry forward locating Hohenlohe’s left flank.

Around Jena, Brunswick’s troops are overwhelmed and outmaneuvered as Lannes flanks them on the right. Wartens however, attacks LaSalle, Murat’s rearguard threatening the rear of their column.

Wartens destroys LaSalle’s small force and pushes on to Neustadt assaulting another cavalry division of Murat. Blucher attempts to help the Prussian forces around Jena but Lannes has outflanked him on the right and the battle for Jena goes poorly for the Prussians. Scharnhorst is forced back, Orange is devastated and Blucher barely survives the battle.

Hohenlohe remains inactive and allows the French to advance forward against his newly formed line running from Zeitz to Zwickau. Brunswick requests help from Hohenlohe and asks for General Kalkrueth to return to him. Kalkrueth, chafing at Hohenlohe’s lack of aggressiveness, tries to contact neighboring Prussian divisions to assist him in an assault on Davout’s Corps before the rest of the French Army comes forward. However, Zechwitz following Hohenlohe’s order to remain on the defensive, will not abide. With Kalkrueth restrained and Hohenlohe inactive, Brunswick’s forces are encircled and almost completely destroyed.

Wartens attacks the last remaining cavalry division in his way west of Neustadt. He is soon to be joined by Saxe.

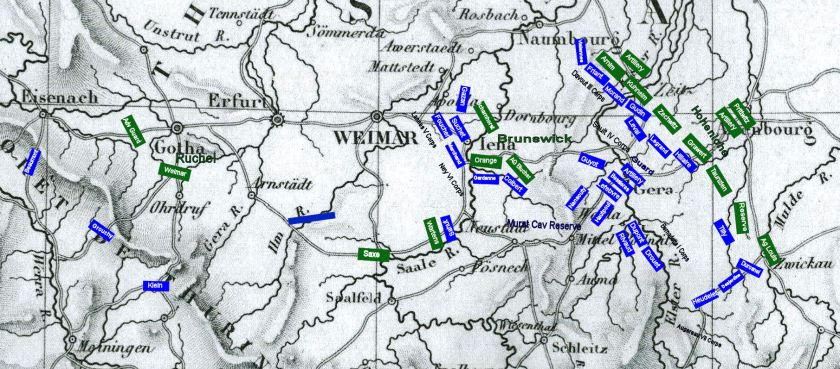

The morning of October 18 brings clarity to a somewhat confusing situation. Napoleon’s main forces are poised to attack Hohenlohe at Zeitz. Ney and Lannes concentrate on the remnants of Brunswick’s divisions around Jena. Murat is forced to turn about-face and deploy against Ruchel who is attacking east into the rear of Napoleon’s army.

Weimar and the Advance Guard realize that there is no use holding Gotha any longer and march east with Jena as their objective. Saxe’s Prussians push back Sahut’s French cavalry and destroys his command.

Meanwhile Wartens attacks Marshall Ney’s forces. It is a grinding and attritional battle at the road junction West of Neustadt. Marshall Ney’s forces have been fighting now for two straight days and are weakening. Lannes on the other hand continues maneuvering to press the remnants of Brunswick’s units.

At Gera, Napoleon directs the general concentration of the French Army to assault Hohenlohe.

By midmorning Napoleon has his forces ready to go. Augereau attacks the town of Zwickau and forces the Prussian Army Group Louis to retreat north. Hohenlohe’s left flank has been turned. A grinding attritional battle occurs all along the line as Hohenlohe tries to make up for his earlier timidity by unknowingly assaulting at the same time Napoleon orders his troops forward. Hohenlohe hopes to break through to Brunswick but is unaware that Brunswick’s forces have already been routed.

Brunswick is in a trap and abandons his troops to escape to Naumbourg in an effort to reestablish communications with Hohenlohe. Lannes makes a critical error by stopping his attack at the moment it could be most decisive. Had he continued to press forward, he would have closed the route to Naumbourg and captured Brunswick likely ending the war. Instead he feels that the Prussian forces in front of him have been defeated and decides to march on Weimar to secure the road north. Ney continues to fight Wartens. Weimar and the Prussian Advance Guard continue their march towards Jena.

Murat’s cavalry divisions out in Gotha finally probe the town finding no Prussian forces and then send units in all directions to try to reestablish contact.

At the road junction West of Neustadt, Ney’s forces are pushed to the breaking point and retreat. The about-face and reverse march by Lannes is fortuitous since he arrives full of fight at Jena before Weimar and the Advance Guard can take that important position.

The remnants of Blucher’s forces flee northward trying to escape what appears to be certain capture by the swarming French forces.

The main battle at Zeitz is slowly unfolding in Napoleon’s favor. Hohenlohe is being pressed on all fronts and his left flank has collapsed. Augereau marches from Zwickau to Altenbourg which is behind Hohenlohe’s lines. In the center and the right wing, a battle of attrition is occurring but Napoleon still has reserves and Hohenlohe has few to throw into the battle.

At Jena, Marshal Ney strives to hold against Wartens and Saxe while Lannes now fends off Weimar and the Advance Guard. To the East, Bernadotte and Augereau start to break the Prussian left flank. The Prussian divisions of Zechwitz and Taunzien are routed. The Reserve division of the Prussian army tries to valiantly hold on the left flank but is greatly outnumbered. It is at this crucial moment that Napoleon decides to launch the Imperial Guard with follow-up from Murat’s two remaining Curraissiers divisions. It is perhaps the most critical and decisive decision of the campaign!

While vicious fighting continues around Jena, Ney is forced to retreat north but Wartens and Saxe are too exhausted to pursue. Lannes checks the advance of Weimar and the Advance Guard but his units are also quickly becoming exhausted from incessant marching and fighting.

At the battle of Zeitz, the Imperial Guard ruptures the center of the Prussian line. Bernadotte and Augereau continue to turn the Prussian left flank and force the Prussian Reserve division to retreat. A giant hole in the center of Hohenlohe’s line combined with the collapsing left flank spells the end for the Prussian main army.

Namsouty and Hautpoul of Murat’s cavalry corps pursue the fleeing enemy. The Prussian Reserve tries to act as a rearguard to allow Prussians to escape towards Leipzig. General Kalkrueth, who has fought a tremendous action on the right flank of the Prussian line, is now outflanked and overwhelmed.

As dusk comes, Brunswick realizes that his Prussian Army has been shattered. Although there is much fighting still going on around Jena where the Prussians are starting to press the French back, no significant organized forces remain with Hohenlohe or Brunswick.

As dusk comes, Brunswick realizes that his Prussian Army has been shattered. Although there is much fighting still going on around Jena where the Prussians are starting to press the French back, no significant organized forces remain with Hohenlohe or Brunswick.

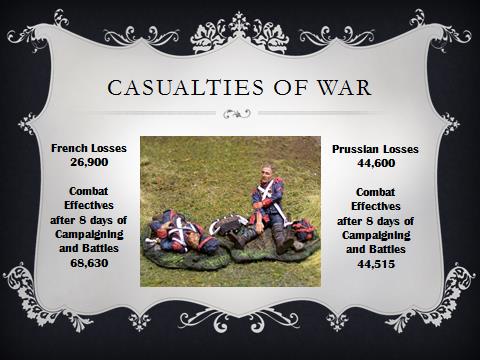

By nightfall, Brunswick asks for an armistice. His units are shattered. The Prussian line around Jena is now threatened in the rear by Grouchy and Beaumont who have marched from Gotha and now are arriving at Jena. Brunswick realizes the situation is hopeless. After signing the armistice, he receives word that the Russians have crossed the Vistula River in an attempt to come to his support!!

The Post Campaign Debriefing

All participants in the 1806 campaign learned very valuable historical lessons. Lack of instant communications and precise information about opposing forces presented them with serious gaps in their knowledge to make competent decisions about future courses of actions for their forces. Given the length of the command cycle, they were often asked to make decisions without any direct input from higher commands. The player whose role was Napoleon commented in our post campaign debriefing,

“I know there was some grousing among the subordinates about the lack of “Big Picture” updates and sharing of intel down the chain of command. This has been deliberate given the necessary time delays involved in 19th century warfare.

It’s highly unlikely I can tell a corps commander something tactically useful that he won’t know better through his own observation, given that anything I can get to him will be between 18 and 48 hours old.

No, they are MARSHALS OF FRANCE!!!, Dammit!!

I wanted them to get in an environment where they were comfortable acting as best they saw fit based on local conditions with occasional pithy input from Nappy at key points. In particular, I did not want occasions of Marshals failing to act while they waited on permission from me.

Overall, I think my subordinate commanders have all done a fine job. If everyone hasn’t been a Patton or a Rommel, there’s no evidence I’ve been afflicted with any McClellans, either.”

Before the campaign started, I gave players a copy of the Principles of War to use as guidance given that this was going to be a very unique experience for them as gamers. In the post campaign debriefing, I used those same Principles of War to demonstrate why the French won and the Prussians lost.

Objective – the French stuck to a clear objective which was to defeat a portion of the Prussian Army with overwhelming forces.

Offensive – the French were almost always on the attack the whole campaign while the Prussians were in a reactive and a defensive stance most of the time

Mass– the French concentrated overwhelming forces at the decisive battle. The Prussians, indecisive and reacting to French maneuvering, were dispersed throughout the campaign

Economy of Force– the French occupied Ruchel with fewer forces by the middle of the campaign allowing them to concentrate superior forces in the decisive Eastern sector.

Maneuver– the French outmaneuvered the Prussians to attain the central position. This shortened their command cycle while fatally prolonging the Prussian command cycle.

Unity of Command– the French were directed by Napoleon to a single focal point. They also had much more communication between corps and division commanders than the Prussians allowing more coordination between individual units.

Surprise– the French were able to decisively attack the Prussians at the time and place of their own choosing while Prussian units were not concentrated.

Simplicity– the French plan was direct and simple; Feint left and strike on the right. The Prussians never seemed to develop a plan of the campaign other than being reactive to French maneuvers.

I hope you will all give Le Vol de l’Aigle a look as it provides fascinating insight into the dilemma of Napoleonic era commanders trying to orchestrate large armies through complex maneuvers to achieve a decisive battle despite immense fog of war and lack of instantaneous communication. All the participants felt this was a tremendous experience. They now better understand why 19th century commanders such as Richard Ewell failed to press Cemetery Ridge on the first day at Gettysburg and why McClellan might have been so cautious during the Peninsula campaign. Even Napoleon made blunders during several of his campaigns which is why he often thought that he preferred a lucky general more than a good general. This game, better than any wargame I have ever played, puts you in the shoes of a Marshal of France or commander of coalition forces. Embrace the experience and try it! You will not be disappointed.

My actions were purposely historical. Resting my troops let Soult get ahead of me on the axis of advance and take some of the casualties for a change. Davout? Who the hell is he to rat me out to Napoleon? Davout, The Glory Grabbing Chicken. My night march after leaving Soult’s flank exposed to observation by Prussian scouts was BRILLIENT damn it. No other player had the moxi to play a night march! My timing was perfect. My Finding, Fixing, and F-ing attack on the Prussian left was the Coup de grace of the entire campaign. And that is why I am King of Sweden.~Bernadotte

Great AAR, with nice maps and narrative! Your comment about the Prussians apparent lack of a plan is spot on – while hindsight is 20/20, it seems remarkable that the Prussians did not plan to move forward and use the natural obstacle of the Foret De Thuringe range to canalize the French advance. Blocking the passes in the west and center with small forces, for example, would have enabled a concentration against the French as they debouched from the passes near Schleitz. Again, great stuff; looks like it was fun!

Great summary article. As one of the French players, I would like to add that the total lack of communications from Murat after day 3 lead to a number of mistakes that should have not happened. There was no way to know what was happening on the other front unless the leaders or Napoleon sent word. I was operating in a vacuum most of the time. Overall it was very enjoyable and we should figure out a way to do something similar again in the future.

Paul F

Fantastic report, thank you.

I am glad you enjoyed the game both as players and as an Umpire.

I ran yesterday my 26th campaign as an Umpire, (november 1805, a few days before Austerlitz, with a modified set up and OB from Volume 2), face to face with 8 players, and the amount of fun I get with every campaign is just not going down.

I have this system and am looking to run a campaign. An article on advice for umpires would be very well recieved!

‘Napoleon’ here. Overall I was extremely pleased with how the campaign developed. Fortunately for my peace of mind I was blissfully unaware of several dangerous moments (such as Soult’s exposed position) but having taken part in some similar kriegspiels in the past I wanted to be certain to avoid micromanaging the battle.

I tried to keep things simple and keep every part of the army close in hand and mutually supporting. I expected the corps commanders to act appropriately within their area without waiting for detailed instructions from the higher command, fuly expecting that sometimes this would not work. I expected the balance sheet to work out in our favor, however, and it did. I saw no egregious blunders. Even Murat’s confusion at the beginning worked out in the end and his drive played a key role in protecting the rear and keeping the Prussian army divided until it was too late.

It was a very satisfying experience and extremely educational. Thanks, Harvey!

I am in agreement with Mr. Makowski: I have vol.3 and am itching to run a campaign but would benefit by an article of tips and suggestions from Mr. Mossman or others with experience. Any hope of such a piece? Thanks for a great AAR!

Bob, It is on my list of articles to get to this year and will hopefully include my handy dandy Excel spreadsheet for tracking morale, Fatigue, combat losses, etc. that I used for this campaign.

Thanks! I’ll keep an eye out for it.

Please include me the next time you try one of these games!!!!

Excellent AAR.

As the Umpire, how and when did you communicate effective strengths for units to the commanders? Casualties? Morale?