A New Look at an Old Favorite

Introduction

The Korean War: June 1950-May 1951 is a simulation of the first year of the Korean conflict in which U.N. (but, overwhelmingly U.S.) forces went head-to-head with the North Korean People’s Army and Chinese Communist Forces.

It’s a moderate complexity game that can take from two hours to play, for a small scenario, to 15+ hours for the campaign game. The game contains units for American, British and other United Nations countries (collectively referred to in this article as “U.N.” forces), Nationalist Chinese (Formosa/Taiwan), and Republic of (South) Korea (ROK) forces on the allied side, and North Korean People’s Army (NKPA), Chinese Communist Forces (CCF), and Soviet Union (USSR) forces on the other side.

The game is played in a maximum of 12 Game Turns with each Turn representing one month of real time. Each Game Turn is further broken down into two Action Phases, each representing approximately two weeks.

Components

The components are average for a mid-1980’s game. The map is functional, legible and without any significant discrepancies or misprints. The pieces are colored such that it is quite easy to distinguish between U.S., U.N., South Korean, North Korean, Russian, Nationalist Chinese and Communist Chinese units. The pieces are also quite durable. (I once accidentally spilled an entire glass of iced tea into the counter tray; I then towel dried the counters, separated them and let them air dry for 24 hours… they’re as good as new). Two informational inserts contain most of the commonly used charts for easy reference, as well as including them on the game maps themselves (i.e. combat charts, etc.). I doubt the game map would stand up to the “iced tea” test, but one wouldn’t expect that level of durability from a paper game map anyway.

Rules Organization

The rules are well organized and fairly comprehensive. One of the most outstanding things about this game is the fact that after countless hours of play, neither I nor my gaming comrades have found any significant holes in the rules at all (see “House Rules” under the “Player Aids” section for the few minor rules items that we felt needed tightening).

Setup

If you’ve read any of my other reviews, you’ll know that the thing I hate most in the gaming world is confusion or ambiguity in game setup instructions. The Korean War scores an A+ in this category. The setup instructions for all scenarios as well as the Campaign Game are crystal clear and without error or ambiguity.

Strategic/Grand Operational Aspects

There are several mechanisms built into the game which simulate events and decisions far above the pay grade of a battlefield commander (although MacArthur did his best to insert himself into this decision cycle). These are decisions made primarily by the U.N. player, but there are also a few to be made by the CCF/NKPA player. For the U.N., these decisions all fall under the category of “commitment” levels and determine the allocation of troops and resources to the war.

Imposing restraint on the commitment levels is the “Global Tension” level. The higher the commitment of U.S. and enemy resources, the more likely the Global Tension level will increase. If events escalate out of control, resulting in World War III, the CCF/NKPA player scores a “Decisive” victory, so it is incumbent on the U.N. player to manage these levels wisely.

At the start of the campaign game, three Commitment levels must be assigned starting values (and managed or adjusted each game turn thereafter):

- Intervention Level – Represents the U.S. commitment to deploy troops and naval and air forces to the war. A higher Intervention level pumps up the reinforcement schedule, but also (potentially) pumps up Global Tension.

- Rules of Engagement Level – Determines how far north the U.N. player may employ “strategic” air missions (supply and movement interdiction). The further north you go, the more effective the interdiction and the more likely to have a negative impact on Global Tension.

- Mobilization Level – Governs three important U.S. capabilities. First, it determines the speed at which destroyed U.S. units can be reconstituted and sent back to the front. Second, it represents the call up of U.S. National Guard divisions and schedules their deployment to Korea. Third, it determines the number of U.N. Amphibious operations (Assaults or Evacuations) that can be executed each turn.

These levels can all be adjusted (upward) during the course of the game, but the initial Intervention Level is super important because its escalation is somewhat limited (i.e. starting the game at Level 4 and escalating later to Level 5 does not get you the same amount of reinforcements in the same amount of time as if you’d begun the game at Level 5).

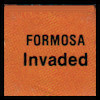

Another political kind of decision facing the U.N. player is the option of inserting Nationalist Chinese Divisions into the battle. The Nationalist Chinese were the losers in China’s vicious civil war and went into exile on the island of Formosa (Taiwan). World opinion was divided on who should be recognized as the “official” government of China, with the U.S. and other western countries insisting that the Nationalist Chinese on Taiwan were the only legitimate government. So, the decision to bring these forces in from Taiwan would have political repercussions, represented by Global Tension in this game.

The CCF/NKPA player, to a much lesser extent, has “big picture” decisions to make. There are game rules that determine when Chinese and/or Soviet intervention can be called for (mostly based on U.N. combat unit proximity to Chinese and Soviet national borders), however the timing of the actual deployment is up to the CCF/NKPA player. For example, if the CCF roll successfully for Limited Chinese Intervention on turn 4, they may delay actual deployment of these forces until turn 5 or 6, etc.

In addition, the CCF player may opt to launch an invasion of Formosa (Taiwan) to forestall any possibility of Nationalist Chinese divisions being deployed in Korea (i.e. they’ll be on Taiwan defending their homes instead!).

The initial selection and management of these levels and options adds another dimension to the game. Decisions here have far reaching consequences on the battle field. This, in itself, gives the game quite a bit of replay value.

If you like games with some depth, rather than just odds-chart combat contests, you’ll really appreciate the additional layers in the game system.

Operational Aspects

It’s great that the rules are organized well and the setup instructions are clear, but if the game does not play well, it’s all for nothing. Fortunately for us, The Korean War campaign game is one of the most intense, competitive and engaging games ever designed. The action is tense and continuous. Here’s a brief outline of the basic flow of the game:

- A powerful North Korean force, complete with armor assets and loaded for bear, invades South Korea. The South Koreans, along with most of the western world, are caught by surprise. The country’s defenders include only depleted strength, screening forces that are brushed aside by the ferocious assault.

- The South Korean player is hard-pressed to stem the tide of invading North Koreans. Fresh NKPA divisions continue to push south-ward. American reinforcements begin to arrive in the southern tip of the country (Pusan), albeit in drips and drabs. But is it too little, too late? As the defensive perimeter shrinks, the outcome is difficult to predict. U.N. options include the possibility of getting Nationalist Chinese Reinforcements or the use of Atomic weapons. Both of these options, while having an immediate defensive benefit on the battlefield, have longer term consequences that may prove fatal to the allied war effort. This phase of the game will end with either the collapse of the invading North Korean army, or with the Americans and South Koreans being driven off the peninsula, losing the game.

- Assuming the game has not ended in a North Korean military victory, the U.S./ROK (and other U.N. forces) will switch to the offensive and rush to annihilate the retreating North Koreans. Powerful American reinforcements are now flowing into the country. It is imperative that the entire invading North Korean army be trapped and destroyed. Flanking maneuvers, like the historical amphibious landing at Inchon, should figure prominently in allied strategy. Finally, the U.N. player must decide whether or not to invade North Korea and, if so, in what strength and configuration?

- Assuming the U.N. player has decided to invade (the most likely scenario), it’s a race against time. Objectives along the Yalu River (the border between North Korea and China) must be secured rapidly before the Chinese decide to intervene militarily. The extreme northeast corner of North Korea, which contains 3 objective cities, also shares a short border with the Soviet Union. The closer the U.N. gets to those borders, the greater the likelihood of Chinese or Soviet intervention. If the requisite number of cities can be secured, the game will end in a U.N. victory. If not, then most likely, the U.N. forces will be facing an avalanche of Communist Chinese Forces.

- If the U.N. is not able to win a military victory, they will be in a desperate situation, fending off attacks on all sides by a Chinese Army group that will rapidly grow to 42 divisions. It’s now the U.N. player who must save his troops from annihilation. Will the retrograde movement (i.e. retreat) be successful or will the entire American 8th Army be surrounded and captured or destroyed?

- U.N. forces retreating from North Korea into South Korea, although saved from encirclement and defeat, must eventually stop running and turn to face their pursuers. U.S. 8th Army must be instilled with confidence and fight back. As the Chinese formations get further and further away from their sources of supply, they will be vulnerable to aggressive U.N. counterattacks.

- If the game reaches this final stage, it becomes a contest to accumulate victory points (awarded for controlling certain cities). It’s possible that the Chinese invasion will be so successful that the original South Korean objectives can be captured, netting the CCF/NKPA player a military victory. But most likely, the game will end in a somewhere along the historical DMZ.

Notice that the above outline contains several points at which one player or the other can win a military victory. Also notice that, assuming the game does not end in a military victory, both players have the opportunity to test their offensive and defensive talents. How many games give you the opportunity to go from being the offensive player to the defensive, then back to offense again… and maybe back to defense after that?!? If you’re the CCF/NKPA player, you’ll probably experience that sequence of events. It’s just one of the many great features of this game.

The campaign game is always a nail-biter! Between two players of equal skill, the final outcome will usually be decided in the final turn or two. After 20+ years of playing this game, I’ve never played a game that wasn’t up for grabs at least until the last two turns. Many times it was undecided until the last few minutes of play!

Movement/Combat

Both armies are regulated, for purposes of movement and combat (and certain other operations, such as Entrenchment), via “Operations” and “Action Points”. Each turn, players take turns rolling dice to see how many “Operations” they can execute. An Operation, generally speaking, represents one unit performing movement and/or combat. Each time a player rolls the die, he may be granted from 0 to 3 Operations, so one can never be sure exactly who will be moving next, and how much activity will be allowed. It’s kind of an expanded version of the “chit pull” system common in many board games.

The exact number of attacks or movement points that can be expended is governed by the 3 “Action Points” allowed per Operation. For example, under normal conditions, a unit may expend 1 Action Point to spend 4 movement points, then spend a second Action Point to attack, then a third Action Point to move again (assuming the attack successfully removed the obstacle of the defending unit). It could also attack, move, then attack again. Or spend all 3 Action Points on movement, etc.

The laws of Probability being what they are, the Operational allowances usually balance out over the course of an entire game. But on any given turn, the Operational sequence can have a dramatic impact on the ability of each side to execute their operational plans.

Combat in The Korean War is a fairly standard business with combat odds ratios, supply status , armor and air support, and defensive terrain modifiers, along with a die roll, determining a point on a combat matrix that decides the resolution of the battle. Combatant units may be eliminated, degraded, and/or forced to retreat. Destroyed U.S. and U.N. units may be “reconstituted” and brought back into play after a delay of a few Action Phases, while ROK, NKPA, CCF, and USSR units are permanently destroyed.

Supply/Logistics

The game’s supply rules are appropriate for the scale of the game and are not onerous, as can sometimes be the case. I know that real war is primarily a logistics exercise, but this is not real war; it’s a game. And games that are primarily logistics exercises appeal to a smaller segment of the gaming community. The Korean War will appeal to a much broader segment of gamers.

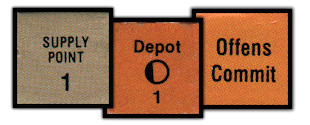

In a nutshell, players are required to position Supply Depots on the map and to provision these Depots with “Supply Points” that can be expended. The more points expended, the more powerful the Depot. An “Accelerated” or “Offensive” Depot acts as a force multiplier, effectively multiplying a unit’s attack strength by 1.5 or 2, respectively. Conversely, the limiting or absence of supply will reduce a unit’s attack strength to ½ or ¼. Players will often agonize over decisions about supply allocation when their forces are located on multiple, separated areas of the map. You can beef up one sector at the expense of the others, or try to balance the allocation.

Supply is a key consideration that will directly impact combat operations, but it’s managed beautifully and does not detract from the enjoyment of the game at all.

Air Power

With the exception of a special rule for the very first Action Phase of the game, only the U.N. player has air power. Air units are allocated between tactical (Close Air Support) and operational (Interdiction) missions, as the U.N. player sees fit. As you would expect, Close Air Support provides a direct, albeit limited, benefit to U.N. combat actions, whereas Interdiction hampers the enemy’s supply and movement capabilities on a province by province basis. It’s fairly abstract, which is a good thing at this scale, and does not bog the game down with air combat minutiae.

h2>Scenarios

There are five non-Campaign scenarios:

- 1. The Invasion of South Korea – Identical to the first four turns of the Campaign game, but without the political decisions.

- 2. The United Nations Strike Back – The U.N. final defense of the “Pusan Perimeter”, the U.N. breakout and counter-offensive, and the aggressive northward pursuit of the retreating NKPA.

- 3. The Chinese Intervene – The initial, massive CCF offensive against 8th Army along the border between North Korea and China.

- 4. The United Nations Resurgent – After the rout of 8th Army and its retreat south of the South Korean capital city of Seoul, the U.N. regains it equilibrium and, under aggressive new leadership, launches offensives which drive the enemy out of South Korea.

- 5. Defeat Into Victory – This is a combination of Scenarios 1 and 2.

These are all very competitive scenarios, which pretty closely parallel the different operational phases of the campaign game (as specified in the bullet points for “Operational Aspects”, above).

Most games at this scale provide smaller scenarios so they don’t scare off the “2-hour attention span” crowd. Unfortunately, I’ve found that most short scenarios are dull and/or unbalanced. It’s as if they were just thrown in to provide an alternative to the full length game, without regard to playability or play balance (which is probably true in most cases).

Once again, The Korean War is the exception to the rule. Most of the scenarios are quite competitive and tension filled. The one exception (maybe) is the “United Nations Strike Back” scenario that, although it models that period of the war quite well, really does not provide a “fun” game for the CCF/NKPA player, at least in my opinion. Could just be personal bias: I hate any game that has “exit units off the north edge of the map” as a victory condition. To me that’s not a war game as much as a mobility exercise, as your units make ridiculous maneuvers to circumvent enemy units in their mad rush to get off the board… never mind that they’re leaving half the enemy army in their rear. While the “Chinese Intervene” scenario has a bit of “exiting off the map edge” thing going on, it doesn’t interfere with player behavior as much as in “United Nations Strike Back”. Try playing them both and you’ll see what I mean.

Although the Scenarios are good, the Campaign Game is really where it’s at. It’s hard to go back to playing the scenarios after you’ve run through the Campaign once or twice, although I still find the scenarios a great teaching aid for new players, and a necessity for any type of single-sitting or tournament play.

Winning the Game

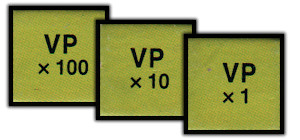

Each of the five non-Campaign scenarios has its own victory conditions, usually involving the accumulation of Victory Points. In these scenarios, Victory Points can be awarded for controlling cities, destroying enemy units, or exiting units off a particular map edge.

In the Campaign game, victory points are awarded only to the U.S. player. Victory Points are gained by controlling victory point cities (as specified by the numbers on the map), and are accumulated from turn to turn. Victory Points can be lost due to Global Tension. For each Global Tension Level, 1 to 6, subtract five Victory Points from the U.N. Victory Point total.

There are three ways victory is decided in the Campaign game:

- World War III – If the Global Tension level reaches 7, the game ends immediately in a CCF/NKPA “Decisive Victory”.

- Military Victory – There are certain geographical objectives (i.e. cities) which must be controlled by each player in order to claim a Military Victory at the end of any game turn.

- Game Turn 12 – If the game goes the distance, the U.N. player’s Victory Point total determines the level of victory (i.e. “UN Decisive Victory”, “Draw”, “NK Marginal Victory”, etc.).

Unlike many other games, the Victory Point range for a “Draw” is rather narrow, so this is not a common outcome. In the vast majority of games, one side or the other will achieve some level of victory (Marginal, Substantive or Decisive).

Summary

By every measure that you could possibly set as the “gold standard” for a military board game, The Korean War: June 1950-May 1951 meets or exceeds the standard. Designer Joe Balkoski really hit a home run with this game. I surveyed my gaming group on Long Island, NY, asking them to list their top 10 favorite games. Only Hannibal: Rome vs Carthage scored higher than Korean War as a group favorite.

Some of my favorite aspects of the game are:

- High replay value. Each game I’ve played developed and ended quite distinctly from all the other games, i.e. different winner, type of victory, level of victory, etc. I’ve seen games end up with the Chinese well into South Korea, and other times with the CCF virtually destroyed and U.N. units all over North Korea, as well as Military Victories for both sides and, of course, World War III due to excessive Global Tension. It’s not that the game system fosters random results. It’s more the fact that the variety of strategic, operational and tactical options allows for a wide range of results, much as the real war could have.

- A simple movement and combat system.

- Low counter density (even when a zillion Chinese units appear, it’s still manageable because there’s no stacking for the Chinese; it’s a max of one unit per hex).

- Continuous action (with the possibility of a brief lull in the action at the point where the U.N. is deciding the right moment to cross the 38th Parallel into North Korea).

- Both players are fully engaged at all times.

- Challenging, competitive game scenarios.

- FUN TO PLAY (we often forget about this measure of game quality).

Some gamers like certain games because of the historical period (i.e. Civil War buffs like Civil War games). Although my father served in the U.S. Navy during the Korean War, I am not and have never been a Korean War buff. So it’s kind of interesting that my favorite military history book is “The Forgotten War: Korea” by Clay Blair, and my favorite military board game is “The Korean War: June 1950-May 1951”. I suppose the military and political circumstances of the period make the Korean War such an interesting subject and, in that sense, this game is an accurate reflection of the conflict. I can’t recommend this game highly enough, and hope this review will encourage others to give it a try.

Glad I found this website. Excellent reviews on two of the games I own, Korea and Vietnam. Although I have not played through an entire Korean campaign I have done so with Vietnam and it is an engrossing game.

In its day Victory Games made some of the best and most realistic games on the market and I own quite a few of them which I play through Cyberboard.

Paul, Glad you enjoyed my articles. You really should make time to play the entire Korean War campaign game. It’s the most entertaining and competitive game that I’ve ever played. Thanks, +Mark

Great summary of a great game.

By the way, I should say that I’ve been a consim player since the 1970’s and Joe Balkoski is my favorite game designe. I’ve been thinking about doing VASSAL modules of some of his neglected titles that all use similar game mechanics to Korean War: these are Omaha Beachhead, St. Lo, Light Division, and Against the Reich. (The Fleet series and the GCACW series already have active VASSAL development.)

I’m working on a VASSAL module for Korean War that includes a completely redrawn map and game pieces. (Scans of the original map and counters just are not suitable for adaptation to VASSAL IMHO.)

I hope you won’t mind my asking for some input.

How important are historical unit designations?

It appears they are not really essential to the game (as the rules mention in a few places). My idea for the module is to use only generic units, by type, size, and combat factors.

How important are map labels?

In redoing the map for VASSAL, I am thinking about not labeling any cities or terrain features. The reason is because imprinted text on a VASSAL map becomes illegible when zoomed out, so it just becomes distracting “text clutter.” Also, my feeling is that wargame maps should primarily be game boards, and they are not really “maps” in any useful cartographic sense (the hex grid, after all, already distorts the terrain). There would be a gazetteer for locating the 20-odd cities, and the Air Theater Display for identifying provinces.

Towns would not even be included on the map, since they have absolutely no effect on game play.

Would you or anyone in your gaming group be willing to playtest this VASSAL module and provide input to its development? Sessions would be live play on VASSAL with voice communication by Skype or GMT’s Ventrillo server.