Game Design by James M. Day

GMT Games LLC

Review by Mitchell Freedman

The box cover says Iron and Oak is a game of “ship-to ship combat during the American Civil War. “

The cover is far too modest. Its really a whole lot more.

Iron and Oak is a game of naval combat, with several scenarios in the “brown water” rivers and bays where navigation can become a problem. So can the enemy forts that go on the edge of the map and can use plunging fire on the ships below.

Players might run into shoals and have to get their ship re-floated, or they could encounter mines or other obstructions, or powerful currents which can carry their ships where they don’t want to go. There are damage control parties, tables of critical hits, and – perhaps most important – die rolls which determine not only the results of combat, but whether a captain can move his ship at all.

Bad captain, green crew, shallow water…what could go wrong?

Then there are “what if” match-ups you can design yourself between ships which never met, as well as actual battles between ships which did engage in combat. And, there are scenarios for a long campaign game where all the ships which survive the initial battle are available for the next fight. Or to go into dry dock for repairs.

If all of this seems like enthusiasm is running wild, I have to admit I really enjoy playing Iron and Oak. It’s one of those games that you can go back to again and again, and never have the same battle twice.

There are some things in this game that may strike players as odd. Oceans and rivers aren’t really gridded in neat rectangles – five across and five down – and the requirement that ships exit the board only from a single box can give the enemy a pretty good idea of what the other side is up to.

A player might also find themselves doing more accounting than fighting. Calculating shots is easy, but working to set up repair crews or putting out fires before they spread and the ship explodes can also take time.

All that said, the game works. And works well. The rectangular grids are a fast and easy way to determine range and movement, the better crews will generally do better in a fight, but not always. And, at any time, a captain might not be able to move their ship at all because they failed a roll.

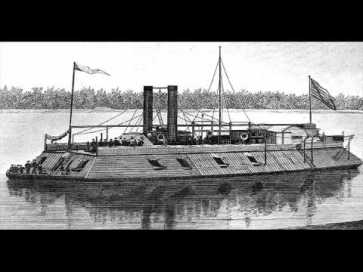

There are other things that add to the fun of this game. Give credit to the artwork, which shows what each ship looked like. Not necessary for playing the game, but it gives a lot of flavor to a battle.

Every ship card also has a number in the upper right corner, which represents what the ship is worth as a battle unit. Gunnery, armor, special weapons….you end up with a way of comparing the relative strength of ships, so you can create your own fleet of any size for a scenario to match the number of available players.

Just for fun, you can match up the Union Monitor and the Confederate Merrimack – the Virginia, if you like – and watch them pound away at each other all day long. Both ships top gunnery is a d-10 (the highest gunnery number in the game) and their armor protection is also calculated with a d-10. Add a repair crew if needed, and they really do reach a stand-off, after sinking any wooden-hulled enemy ships in range.

There are 78 individual cards for ships and forts. Gun size and armor are abstracted, but a little ship icon does show whether you can fire directly across the bow or stern, and if there is a penalty.

For example – its the actual example given in the rules – the CSS Alabama has two guns which fire a D-10 and a D-8. The target it is firing it also gets to roll dice and add any armor protection to weaken the blow. If the firing number is larger than the defensive total, there is a hit. The bigger the difference in those two numbers, the more damage will be done.

Admittedly abstract, but simple to resolve and – over the course of a game – you end up with the kind of results that you likely would have gotten with a more complex calculation of armor, gun strength and position. (Yes, your ships can try and cross the T if you are in the same box as the enemy).

One thing that can make every battle different – including the fight between the ironclads at Hampton Roads – are the cards each player can draw that may change the odds in their favor.

Then there are the 50 Action Cards and 16 Order Cards which players draw at random. Play a rapid fire card to cause more damage, or play a misfire card when you are under attack. There’s even one card that lets you designate another ship in your box as blocking fire from the enemy…a card that is useless if there are only two ships in your little rectangle of ocean.

You can make an argument that those cards are the most important part of the game. If you don’t have the right maneuver card, you can’t move your ship where you want it to go. Another card will let you ram an opponent, or cross their “T”.

There are two orders on each maneuver card – you pick one – but there is only one action on each card in the actions deck. One is often enough. Rapid fire gives you two shots in a row. You can scuttle a grounded ship from your side to keep the enemy from getting victory points. Quick maneuver lets you add plus one to your die roll. while slow maneuver lets you add minus one to an opponent’s movement.

There are restrictions on how many cards you can have in your hand, and getting rid of a card you may not want and pulling a replacement isn’t simple, but it can be done.

I like games where a lot of things can happen, and I like games where the phases of a turn play out smoothly, one step at a time. And, I like to play with some options and some surprises, and where the victory conditions are clear – even if its only exiting a single ship with less than heavy damage.

Like all good games, players can try different strategies in Iron and Oak. Stand off with your bigger ships and fire at long range, or make a mad dash and blaze away at your foe. Some scenarios set turn limits – exit no sooner than turn 20 or later than turn 30 – or give a geographic condition, such as exiting the board from a particular hex.

Both sides know what has to happen to win. It can make for a heck of a battle.

Those things, for me, are the attractions of Iron and Oak. It plays fast, it plays well, and there is just enough uncertainty to make every turn an adventure.

Some of the scenarios – certainly those between just two ships – are for solitaire games or for just two players. Others can be played by two people, but also can easily have three or four players as well.

Happy sailing.

Reblogged this on Burns & Co. Blog and commented:

Civil war naval battles