By Michael Stultz

Designer: Bowens Simmons

Publisher: Mercury Games

Confederate forces invaded the United States of America in the summer of 1863 during the waning days of June. Just two months prior at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Lee’s army had defeated the Army of the Potomac, one of several defeats inflicted on the Union. Lee reasoned that now was the time for a bold strike that might win the war for the South, or at least, procure necessary victuals and potentially gain the recognition and support of one or both of France and England. The Confederate rank and file were confident and self-assured as they struck north in the waning days of June 1863. It was the high-tide for General Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia. The aim was simple: requisition supplies and disrupt Union invasion plans. Lee’s army desperately needed this in the face of an increasingly critical scarcity of food and basic material; and strategically, taking the war onto Northern soil would put the Confederates on the offensive outside their own territory. So, march they did. In the first three days of July, a momentous battle was fought where no one had planned to engage, at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. In those three days, two armies and two nations collided in violent combat. And in those three days, one nation died, another triumphed.

That’s the history. And if you want to replay history using scripted movements and positions, playing across a hexagonal grid, you will not likely enjoy Guns of Gettysburg, designed by Bowen Simmons and published by Mercury Games. But if you are looking for a unique design that takes you into the action of those three days, this is a candidate well deserving of your time.

Paul Comben, a frequent contributor to this magazine, writes about the game that this is a simple but complicated game, one that is a “clever, daring design, but you may not find it to your taste if you really want unit counters, rules with a familiar feel to them, and units marching down the well- trodden roads at the usual time. If you want a touch of the radical however, this is one amazing game.”

I have played Guns of Gettysburg on several occasions recently with various members of my local historical gaming group. I wanted to share my impressions about game play and the design. My goal in writing is to provide a description of the game, its play, the components, and our experiences.

First, the pieces. This is a block game and it comes with a mounted map. It is difficult to judge the scale as unit sizes are abstracted. Suffice it to say that each division or corps is represented at full strength by two or three blocks. There are also cardboard counters used to identify when and what reinforcements arrive, and there are six plastic discs, three for each side, used to mark on the map victory objectives.

Let’s discuss the map. This is a beautiful rendering of the area and it is reminiscent of a 19th Century battlefield map that you might find laid out on a commander’s table inside his tent. It beckons and woos you to study its every detail. It should be poured over and comprehended. It is the heart of the game. The map shows the town of Gettysburg, of course, and the surrounding country side, but superimposed over this map is a grid of polygons that depict areas that are not uniform in size or shape. These areas are drawn and designed in such a way as to capture the topography of the field of battle. Terrain graphics shown on the map (woods, streams, etc.) are cosmetic and do not regulate play. What does are the lines and circles between areas—called positions and endpoints. The sides of each polygon are an area’s bounding positions, and some of these contain terrain types (open, ridge, steep slope and obstructed) that affect movement and combat. Units occupy these positions. This is called occupying “a position.” Positions dictate fields of fire and vision. This in turn affects movement and combat, as one might expect.

Units move from position to position on the map. They do not occupy areas and they do not move from area to area. This is critical to understanding the flow of play. A purposeful player will be rewarded from careful study of the map for the genius in this game is not simply in knowing where the high ground is but in understanding how a position influences the maneuver of your opponent. In the same way that in chess the placement of a piece controls or threatens blocks, the placement of pieces in Guns in Gettysburg similarly controls movement. It is an understatement here to say that one must control terrain favorable to the defense. In order to play the game well, you must take advantage of the terrain features so as maximize the advantage of the defense and to hinder the attacker’s movement, or to threaten a defender’s desires by exercising control over the areas in front of the attackers. This is critical for both sides, for the Union because likely it will play a defensive game, for the Confederates, because the burden of attack is upon it throughout.

If you want to replay history using scripted movements and positions, playing across a hexagonal grid, you will not likely enjoy Guns of Gettysburg. But if you are looking for a unique design that takes you into the action of those three days, this is a candidate well deserving of your time.

As already mentioned, this is a block game, similar in appearance to Napoleon’s Triumph, a sister game also produced by Bowen Simmons. Unlike a Columbia Games or Worthington Games where a block is rotated with each step loss, in this presentation, blocks are low and rectangular in shape, red for the Confederate army, Blue for the Northern, and at full strength, they depict the state flags for the respective units. These flags represent the number of strength points for a block, two flags equals two points, and one flag is one point. When a unit is reduced, its strength is represented by a tattered battle flag. There is a novel mechanism for determining how blocks are reduced in strength which I will discuss a little later. The wooden blocks represent the infancy and cavalry units of the opposing armies.

Three points to note about the blocks is that there are no leaders in this game, there are no artillery units, per se, and the confederates have no cavalry. The blocks are organized for the Union Army into commands that represent Union infantry corps, and for the Confederates, into infantry divisions that are organized into corps (I, II and III).

For me at least, one enjoyable aspect to the game design though certainly frustrating at times for both players is the use of a random, double-blind reinforcement schedule. Although the game provides a time table one could use to duplicate the historical arrival of reinforcements, the default is to use a time track in which “rumor” tokens are mixed in with unit arrival tokens. Each space on the track represents an hour of time, and each turn consists of a minimum of one hour but could include several hours, depending on the number of blocks on the board and whether an attack order has been issued. In a turn, each side flips its respective tokens for every hour that comprises that turn to find out whether reinforcements will be arriving, or whether it is only a rumor, in which case, the player must wait for the next turn. What makes this a fun game experience is that one or both sides may suffer a nervous break-down while awaiting reinforcements. This is especially for the Confederates. If Johnny Reb comes up the Chambersburg Pike early and in force, the Union Army may find itself reeling early in the game. The converse is equally true. If Southern reinforcements are slow to enter the battle, victory may be beyond reach.

And this takes me to another fascinating design feature. The Confederate player must fully control all three objectives by the end of any Union action phase occurring on July 2nd or July 3rd. These objectives appear on the map as stars printed on the map in three different areas. Each is marked by an objective marker, initially in blue for the Union player. They need to be captured by the Confederate player in order for him to secure a victory. However, the Union player has an opportunity in each “Objective Phase” to move these discs to an adjacent area if he has fewer reinforcement tokens and no more than four in total. So, if the Confederate player is fortunate enough to receive strong reinforcements early in the game, which is what he wants and needs, he is faced with the concomitant challenge: the game equivalent of “whack a mole.” Eventually this stabilizes, but this built-in fluidity captures beautifully the dynamic faced by General Lee’s army as they were drawn into an unplanned battle with no clear objective from the outset.

Another intriguing aspect to this game is how it handles artillery. There are no artillery units. Rather, in keeping with some of the abstract characteristics of this design, artillery battle tokens are drawn randomly from a pool specific to each player and used as desired as a bombardment prelude to an infantry assault. Once used, they are removed from play. This forces players to husband resources and to think carefully about when and where to employ artillery. One of the members of our group rightly observed that purists may scoff at this feature of play, but the trade-off pays in fun game play. Essentially, the designer has created an artillery mini-game that plays out before each assault. And did I mention that one cannot just use any artillery token? In order to employ, the token must organizationally match the infantry blocks. If Pickett is attacking for example, he needs his own divisional artillery or artillery from his corps to support him. There are reserve artillery tokens, but these are restricted in use.

In many contemporary military simulation games initiative is handled by a chit-pull system. In Guns of Gettysburg, essentially, the Confederate possesses and retains the initiative unless he places his army under general withdrawal orders. If this happens, it is likely a sign that General Lee and his boys are headed back south. This game forces a player to plan his offensive by announcing at the end of each turn whether your army will be holding, withdrawing, or attacking in the immediately ensuing turn. If an attack is declared, that player must attack in his next turn or forfeit one-half of his available battle tokens (they will recycle back into play later).

It is in the combat phase that the true elegance of the game emerges. Play feels much more organic and less rigid and mathematical than a traditional hexagonal grid. A player must position and coordinate his blocks as they march into position. Where he can march, with what units, and from which positions is often dictated by enemy positions and the lay of the land. Sure, this is true in virtually any war game, but recall that I said a block occupies a position on one side of a polygon and from this position it has a field of vision and projects a field of fire into the area to its front. This sometimes includes an extended front (think of peripheral vision and you get the basic idea). One cannot simply move through an area. One cannot simply move around an opponent’s position and the area into which he projects his field of fire. One cannot always simply move into an attacking position. All movement is directly influenced by the polygons. Their various shapes and sizes model the hills and rough terrain in and around Gettysburg. This game almost has the feel and play of a three-dimensional battle space. To get into position requires an understanding of how the map will compel certain movements. And units move slowly in this game. Other than when reinforcements arrive and are able to travel by road, the infantry marches into position—slowly marches into position as though this were a cavalcade on foot. There are no grand sweeping cavalry charges with horses galloping across a broad field or at the flanks of the enemy. There are no hordes of screaming infantrymen running full tilt at the enemy across eight or ten hexes like you might see in La Bataille games. If there is a “rebel yell” in this game it is only in that last push toward melee. You better plan your moves and plan carefully.

Speaking of close combat and all, this game is bloody. Expect to lose a lot of men. Which is another reason that, when combined with the artillery rules, engagements need to be planned and executed with care. As they generally were at the real battle. Sure, troops reacted in unexpected ways at times, but methodology is incorporated into this design and must be employed if one is to succeed.

I think my favorite design feature to this game is the dice-less combat. That’s right. No dice. Whew. I just hate the fact that an articulate and well-prepared defense or attack can be entirely undone by a bad die roll, as happened recently to one member of our group in the La Bataille de Dresde scenario we played. A team-mate and I were defending a village outside the city, he attacked with a horde of Russians. Those men assaulted and over-ran our artillery, the nerve of them…. but then when we counter-attacked… That characteristic groan was heard when his men failed their moral check, forcing them to retreat as a dis-ordered group out of the village. Now, the moment we were waiting for: we unleashed the French Hussars waiting so patiently nearby. It was a cinematic moment worthy of Cecile B. Demille. Those Hussars went riding around the entire Russian mass, doffed their headgear as they flashed by the Cossacks who decided not to counter-charge at 1-4 odds, and crashed into those craven infantrymen who retreated from the village. That sent what little remained of the lot along with their forlorn divisional leader back to Russia. And soon after that there were no more Russians beating at the door. Vive Le Empereur! I digress…. Back to Guns of Gettysburg.

Yes, I know, dice capture the vicissitudes of military operations. All the same, with no dice, given a block system’s fog of war, the idiosyncratic artillery rules, and the map design, combat calculation is a guessing game. You sort of know what your opponent may have, but not knowing what he may throw down for artillery support is a wild guess. In many ways, this puts you into a position not unlike what a commander faces. You know there is an enemy to your front, but you don’t know the strength of his position until you engage. Conventional game designs capture certain realities better than block games, but in my view, block games are brilliant in how they depict the unknown, and this game is no exception.

My favorite design feature to this game is the dice-less combat

In the combat system, the attacker chooses which block or blocks will attack, which position he will assault, conducts artillery bombardment if he has any, receives counter-artillery fire against his infantry, and those that survive compare their strength number against the defender’s, apply modifiers, and determine if the resulting number one or more. If so, the attacker gains the position. If not, he fails. A lovely creation.

One last observation about the combat system concerns reductions to unit strength. As I indicated earlier, rather than rotating a block to show reduced potency, in Guns of Gettysburg, as a unit absorbs hits, it must either be exchanged for blocks of lesser strength, or for blocks at the same strength level but with diminished capacity to suffer casualties. This is how the design incorporates unit quality into the system. When there are no more replacement blocks, a unit is eliminated from play.

I indirectly referenced earlier that players must decide the operational direction of their army. This is accomplished with “orders” that each player must give to his army at the conclusion of each turn. An army either holds, withdraws, or attacks. Much time is often spent “holding” while maneuvering pieces into position for the inevitable clash of arms. When combined with the random reinforcement arrival track, the game creates a nice ebb and flow to play that I think accurately captures the period: troops take time to get into position, a battle may result when not desired, and because artillery is a limited resource and subject to random selection, a Confederate player especially often finds himself making a difficult choice about where to attack and with what units. By comparison, it can just as easily be the case that the Union player finds himself pressed hard against his entire front without adequate defense resources. If a breakthrough occurs, it can spell doom. I have not seen a general withdrawal order issued by a player in the games I have played, but I have played games where a hole is punched in someone’s line. This can seriously compromise a position, though interestingly, again, I think consistent with the actual battle, an attacker who does succeed in breaking through the defense may not have units sufficiently strong to maintain the gain against counter-attack.

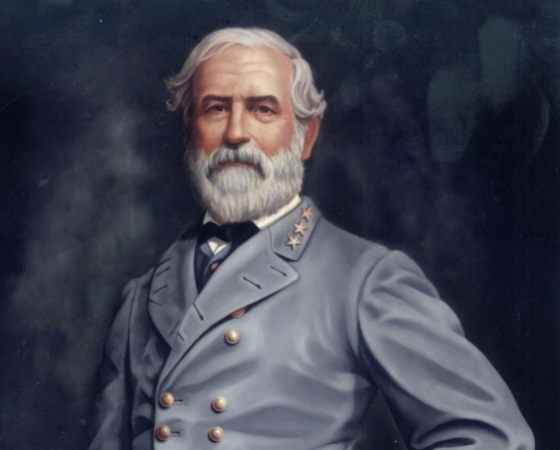

There you have it, my thoughts on this exceptionally elegant design. Guns of Gettysburg is meant to be played and enjoyed. It presents players with a simulation that lifts you from an entirely scripted performance while both retaining strong historical flavor and emphasizing the difficult choices each commander had to make. If your interest is in studying this pivotal battle in exacting detail, in seeing how the battle unfolded each day, you should probably look to one of the other designs in the hobby. However, if you want to be in the commander’s seat and see if Robert E. Lee and his boys could have prevailed, or whether George Meade and his Yankees can successfully stand against the lines of grey, there is much to commend about this game.

About the Author

Michael has been playing military simulation games since the mid-1970s, starting with his first game (which he still has in his collection), ordered from the back page of a comic book. He then quickly graduated to Avalon Hill’s Battle of the Bulge, with the blue American and pink German armies. He spent many long hours sitting with his maternal grandfather listening to stories about military history, especially the War Between the States. Having grown up in Baltimore, frequent trips to Avalon Hill’s row-house headquarters was a necessity. After graduating from college, he attended graduate school then law school before heading out to sea with the U.S. Navy as a Judge Advocate. Twenty-five years and various deployments later, he is still serving in the Navy, but now as a reserve officer. Military history and service is a life-long passion. In his civilian life, he works for the State of Maine’s municipal league.

Michael enjoys grand tactical and operational level games especially, with a particular affinity for ancients, Napoleonic and Age of Reason themes. He also enjoys World War II simulations. His collection is varied and includes both old and new titles, from Avalon Hill, Battleline, and SPI to VentoNuovo, Draco Ideas and Legion War Games.

Michael lives with his lovely wife and two daughters with whom he shares his gaming passion, but in the family-friendly form of Euro games.

Related Articles:

The US Civil War-A BoardgamingLife Review

Gettysburg’s Gettysburgs: A Boardgaming Life Review

A Minié View of Huzzah! – A Boardgaming Life Review

Antietam – Burnished Rows of Steel – A Board Game Review

Bobby Lee: The Civil War in Virginia

Over the River and Through the Woods – A “Grant Takes Command” Board Game Replay

Great look at a very fine game. The last time I played this, poor old Buford waited a very long time for anyone other than Buford to turn up and help out. But that’s the point; neither side can count on anything, and on another day, with another play, it is all different again.

Excellent review!!!